- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

Student-Led Tribute: Remembering Andrew Goodman and Freedom Summer

If not Now, then When? If not Us, then Who? Ramapo College Andrew Goodman Foundation Ambassadors Sarah Glisson and Sydney Mattea bring Freedom Summer to life in the 60th Anniversary Exhibit they coordinated for Civic Engagement Week.

by Liz Mendicino ’26

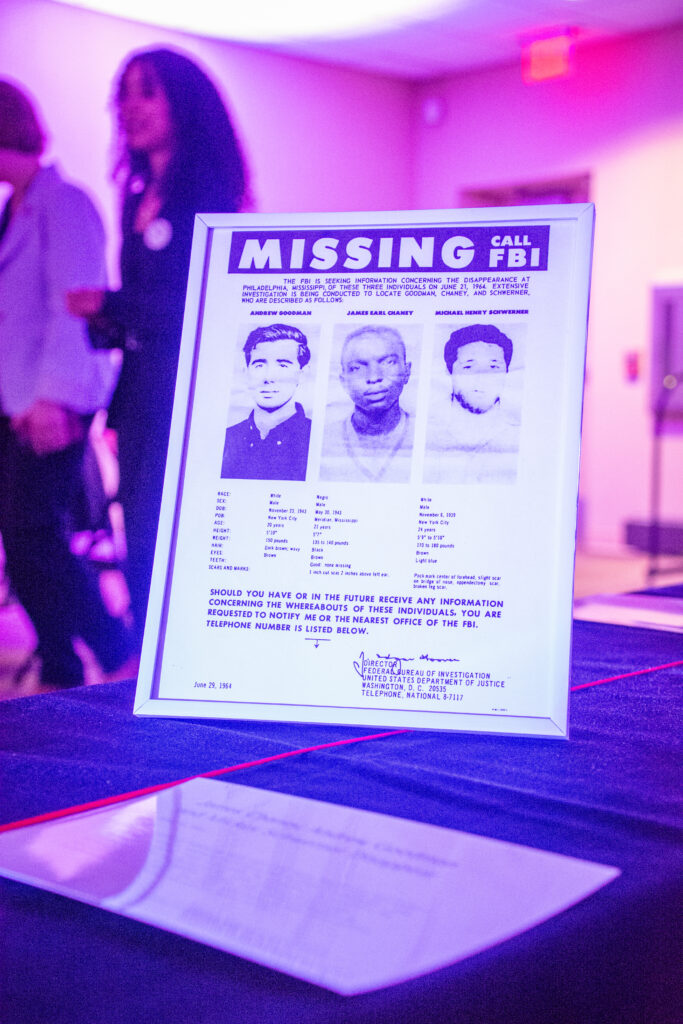

“We really wanted to make sure we were starting at Andrew Goodman and then kind of expanding from there,” said Sydney Mattea, one of the Andrew Goodman Foundation ambassadors who made this event happen. “So showing one of the biggest tragedies that came out of Freedom Summer at the beginning of it, Andy, James, and Michael’s murder. We wanted to start with a piece that was talking about Andy, so we have his original applications to volunteer in Freedom Summer, which is fantastic to be able to read that and see that and really express how much those forms are, like stuff we get. He was a college student and he was trying to do the right thing.”

Andrew Goodman Foundation Ambassadors and RCNJ students Sydney Mattea and Sarah Glisson

The April event, part of Ramapo’s Civic Engagement Week, was a beautiful museum-style exhibit that encapsulated themes of Freedom Summer and its history while zooming in on Andrew Goodman and his story. The back wall was covered in posters displaying various protest messages, each hand painted by Glisson. Lights illuminate the timeline in the middle room, a red string of fate connecting decades of history. A button making table, a typewriter, books from George T. Potter Library, and a video interview with civil rights activist Robert Masters are just a few interactive pieces around the beautifully curated time capsule-esque event.

“This idea and execution from my students. I can’t take credit beyond providing support and advisement throughout it. This is their vision,” said Dylan Heffernan, assistant director for civic engagement.

Andrew Goodman joined the Freedom Summer movement in 1964 to register African-Americans to vote. On his first day, he and two other civil rights workers, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. The Andrew Goodman Foundation was created to honor his legacy and empower young people top become active, engaged citizens who care about democracy and civil rights.

This document was part of the timeline on display and shows three men killed during Freedom Summer, including Andrew Goodman.

“The most rewarding part was definitely the interview with Robert Masters, I get goosebumps every single time I think about it,” Glisson said. “He told us at the end, that reliving these moments, it gets emotional for him and for us it was just kind of putting that notion into place. We’ve told students this entire year that voting is such a luxury, like it hasn’t really been made fully accessible in this country. It’s a privilege and a right that we all have. So to hear Robert Masters and people in his life, like Andrew Goodman, who died for the right to vote, it’s just crazy to us that some students will actively not participate within civics. I understand there’s barriers in place, but like I just get goosebumps, don’t they? People like Andrew died for this.”

“The people who participate in Freedom Summer like Andrew Goodman, they’re just people,” Heffernan said. “You can read their notes. You can see his application. You can see that they didn’t start out as heroes, I mean they are, but they’re not. They’re people, they’re humans, and my hope with this and all the programming we do is show that everyone has that power to make the same impact.”

“I mean Civic Engagement week at its basis is about activism, empowerment, making sure students are aware of their resources, knowing their needs, and also knowing what they’re capable of,” said Mattea. “I think Freedom Summer is such a good basis for that student power and what students are able to accomplish is immeasurable, so I hope this event really can remind students of that. Tomorrow we have an event called Advocacy in Action that I’m running all about student engagement with protesting, different modes of protesting that don’t just involve in-person protesting like infographics and how to kind of engage with your community in different ways in grassroots organizations.”

One of the many interactive displays included a button-making table.

https://andrewgoodman.org/who-we-are/

Andrew Goodman joined Freedom Summer 1964 to register African-Americans to vote. On his first day in Mississippi, he and two other civil rights workers, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan.

Andrew and his contemporaries were young Americans who were committed to changing the world, and joined a movement to take action against injustice. Learn more about Andy, the college student studying theater, and the event that woke the sleeping conscience of a nation.

We are witness to the rise of a diverse and connected new citizenry, one that can forever transform our society and our world for the better. Our ability to spark their passion — today — will result in change, tomorrow. The Andrew Goodman Foundation supports youth leadership development, voting accessibility, and social justice initiatives on campuses across the country with mini-grants to select institutions of higher learning and other financial assistance to students.

Our vision is that young people will become active, engaged citizens who ensure a just democracy and sustainable future. Join us during this critical time for American democracy and help shape the next generation of civic leaders.

Freedom Summer 1964 was a movement led by young people. During a time in our troubled history when the South was still deeply segregated, young people answered the call to make a difference — not just for their futures, but for the generations who would come after them. Whether young people joined the movement because of their parents’ activism, or because they saw posters on their college campuses, one thing was clear: Young people completely transformed the course of history through their advocacy and their commitment to an equitable future. To understand the pivotal role of Freedom Summer 1964, we must begin by understanding why bold action for voting rights for Black Americans was so imperative.

Freedom Summer, or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a 1964 voter registration drive aimed at increasing the number of registered Black voters in Mississippi. The state was chosen as the focus of Freedom Summer 1964 due to its historically low levels of Black voter registration. In fact, in 1962, less than 7 percent of the state’s eligible Black voters were registered to vote. Black Americans often faced violence and intimidation when they attempted to vote. Poll taxes and literacy tests were designed to silence Black voters. With this in mind, over 700 mostly white volunteers joined Black people in Mississippi to fight against voter intimidation and discrimination at the polls.

Like most things in history, the events of Freedom Summer 1964 did not happen in a vacuum. By 1964, the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing. The Freedom Riders had started their direct action against segregated public transportation in 1961, Southern organizers were staging sit-ins to protest Jim Crow Laws, and Dr. Martin Luther King had given his “I Have A Dream” speech at the August 1963 March on Washington as 250,000 people gathered at the Lincoln Memorial. Despite the progress being made, the South remained a hot spot for racial segregation, especially at the polls.

Copyright ©2025 Ramapo College Of New Jersey. Statements And Policies. Contact Webmaster.

Follow Ramapo