- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

The Dangers of Free Speech: Digital Hate Crimes

(PDF) (DOC) (JPG)September 20, 2018

Sara Eljouzi[1]

Hate Crimes in the Digital World

Hate speech on the Internet has perpetuated a free reign to attack others based on prejudices. While some may dismiss the attacks as rants reduced to a small online community, the truth is that their collective voice is motivating dangerous behavior against minority groups. However, the perpetrators of online hate speech are shielded by anonymous creators and private usernames, and, furthermore, their strongest line of defense rests in the United States Constitution:

In the United States, under the First Amendment to the Constitution, online hate speech enjoys the same protections as any other form of speech. These speech protections are much more robust than that of the international community. As a result, hate organizations have found a safe-haven in the United States from which to launch their hateful messages (Henry, 2009, p. 235).

The freedom afforded to online users has ultimately compromised the safety of Americans who are targets of hate speech and hate crimes. The First Amendment was created to protect citizens’ right to free speech, but it has also established a sense of invincibility for extremists who thrive in the digital world.

Hate Speech and The First Amendment

In June 2017, a case arose in the Supreme Court that challenged the limits of free speech. In Matal v. Tam, 582 U.S. __, the court unanimously ruled that they cannot deny the creation of trademarks that disparage certain groups or include racist symbols (Volokh, 2017, p. 1). The unanimous decision triggered a debate about hate speech in relation to the First Amendment. Justice Samuel Alito was among the Supreme Court Justices who weighed in on the conversation. He explained:

[T]he idea that the government may restrict speech expressing ideas that offend … strikes at the heart of the First Amendment. Speech that demeans on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, age, disability, or any other similar ground is hateful; but the proudest boast of our free speech jurisprudence is that we protect the freedom to express ‘the thought that we hate’ (as cited in Volokh, 2017, p. 1).

While this undeniable sentiment forms the democratic foundation of our Constitution, the problem is not only about reciting hateful phrases or creating hostility. Hate speech can in fact incite violence and lead to hate crimes, leaving targeted groups vulnerable. In one case, Ryan Wilson, the leader of ALPHA HQ, a white supremacist group, threatened and harassed Bonnie Jouhari, a Fair Housing Specialist and her daughter (Henry, 2009, p. 239). According to HUD v. Wilson (2000):

Wilson used his website to target Jouhari. Jouhhari’s photograph was posted on the site, and was accompanied by the warning: ‘Traitors like this should beware, for in our day, they will be hung by the neck from the nearest tree or lamp post’. The website also displayed a picture of her daughter, who was labeled ‘a mongrel’. In addition, the website included a bomb recipe, and a picture of Jouhari’s office being blown-up by explosives” (as cited in Henry, 2009, p. 239).

The language used was threatening with blatant racial undertones because her daughter was biracial. Threats of lynching clearly referenced the history of slavery and subsequent ongoing brutalization of African Americans in the United States, further promoting their racist ideals. They made physical threats against her and forever changed her life by publicly targeting her and promoting her as a target. The Department of Housing and Urban Development eventually took action, but “Jouhari repeatedly sought assistance from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The Department of Justice reportedly declined to pursue the matter due to First Amendment concerns” (Henry, 2009, p. 239). Thankfully, HUD’s involvement in the case ultimately led to the removal of the photos from the website. However, this could not undo the harm of victimization Jouhari had suffered. The people who attacked Jouhari and her daughter online became intertwined in their lives. The hate speech manifested into hate crimes that included threatening phone calls and sitting outside of her office for hours, sometimes taking pictures of her. After becoming public targets:

Bonnie Jouhari and her daughter spent years on the run from white supremacists who had launched a vicious campaign of harassment and intimidation in southeastern Pennsylvania. Hopscotching from state to state, Jouhari was unable to return to the career she loved, and her teenage daughter, Dani, became deeply depressed. Dani never got over the trauma, Jouhari says, and sank into substance abuse and homelessness after serving as an Army medic (Rubinkam, 2015, p. 1).

This case is one of many that shows the way online hate speech can lead to personal confrontations and hate crimes that ruin the lives of victims.

Hate Speech and Hate Crimes

Like the previous case with Jouhari, it is important to understand that hate speech and hate crimes can be directly linked:

In hate crime, a person is attacked not randomly, but precisely for being perceived as X. In other words, hate crime identifies, categorizes, and labels persons according to real or supposed features such as sex, race, class, sexual orientation etc. This act of labelling a person as some-one or something is in itself already a linguistic act of positing, an act of denomination and determination that attributes a social status to a person (Posselt, 2017, p. 15).

Although hate crimes involve physical acts, it is motivated by prejudices of the attacker, which are often expressed by hate speech. The motivation of hate crimes is to further a biased ideal and express ideas of hatred that are meant to instill fear in the victim:

Hate crimes do not only inflict injuries on others, they also communicate a certain message on several levels and to different addressees: to the attacked individual and bystanders, to the social group the individual belongs to and to sympathisers of the offender as well as to society at large (Posselt, 2017, p. 15).

What gives hate crimes their label is the message behind them. Their physical acts are harmful, but their power comes from spreading hateful messages and victimizing minority groups. They seek to promote their agenda and recruit others to also share in these extreme views by verbal and physical actions:

If it is true that hate crime “speaks” and that it is precisely the linguistic-symbolic mo-ment that constitutes hate crime in its specificity, then language and speech can no longer be conceived as merely additional features of hate crime, rather they are essential to it. Thus, hate speech would be the general type and hate crime merely a subspecies of it (Posselt, 2017, p. 15).

Textual Analysis

“Due to the proliferation of the Internet and the breadth of its reach, bigoted messages can be communicated with ease and to a much larger audience than ever before” (Henry, 2009, p. 235). Analyzing a website that is established to attack certain groups and promote a racist agenda can shed light on hate crimes in the digital world. The historically racist website Stormfront was created to promote White supremacy, while communicating ideas about the inferiority and necessary fear of other races. The homepage says: “We are the voice of the new, embattled White minority!” (Stormfront website). The objective of the website is to promote White nationalism and, by characterizing themselves as a minority, they are spreading the idea that they are no longer dominant, leaving them vulnerable in society. The people who created the website and the majority of users are White people who reject the idea of “Whiteness as a location of structural advantage, a standpoint, and a set of core values, practices and norms” (Sorrells, 2013, p. 63). They want to justify the website, showing that they need to advocate for the minority opposed to the standard ideal that White people enjoy certain privileges because of their race. The new standard they want to establish is that White people are at risk of becoming obsolete and that society is actively working toward making them powerless.

Create Collective Identity

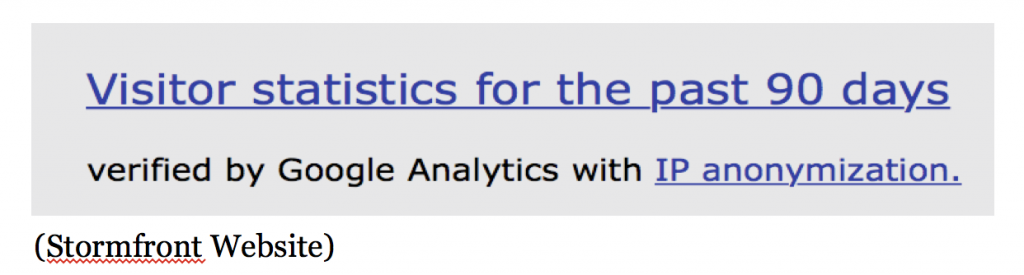

On the opening page of the website, there are multiple forums with various discussions relating to White supremacy that are distinguished by topic or age/gender. The forums “can help convince even the most ardent extremist that he is not alone, that his views are not, in fact, extreme at all. […] Extremists appear to be using the Internet to create a collective identity” (Gerstenfeld, Grant, & Chiang, 2003, p. 40). The forums are usually initiated by a question or concern proposed by one user and anyone is free to respond to it. Members are anonymous, but they directly reply to each other’s comments about similar issues and validate their feelings. Aside from creating unity through forums with hundreds of replies, the website also boasts about the number of users to the site to further reinforce the notion that their ideas are shared by many others. Below is a picture from the website that is found on the bottom of the homepage, welcoming viewers to look at the number of visitors:

However, the number and their perceived growing popularity may not be accurate. “The actual author or sponsor of a site does not always need to be obvious. Therefore, a single individual can claim to be representing a large group, and very few visitors to the page will be the wiser. A webmaster can also bolster the apparent popularity of a site by including a hit counter, which keeps track of the number of visitors to a web page […] and perhaps even by artificially inflating the hit count” (Gerstenfeld, Grant, & Chiang, 2003, p. 40). The website wants viewers to acknowledge that they are part of an online community who shares their views and be unafraid to speak openly about controversial topics. Another way to encourage unity in a more dangerous way is the website’s ability to facilitate meetings in person. There is a private forum that is only accessible to continuing members with information about upcoming events:

The forum wants to encourage members to feel exclusive and give them the power to form relationships. Because it is locked, it encourages regular members to become sustaining members in order to be included in the plans. The meticulous planning and organization of large groups meeting in person can motivate hate crimes and unite individuals with a dangerous agenda.

Spread Fear

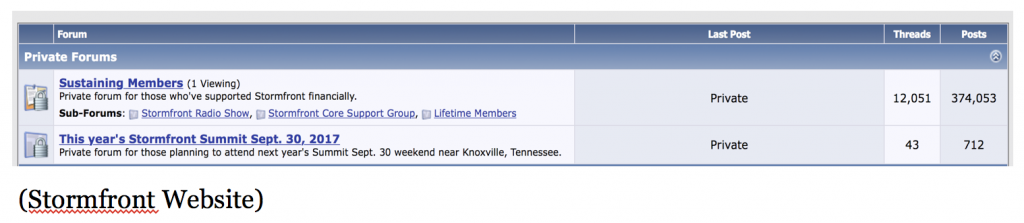

One of the primary objectives of the website is to spread fear about people who are not White and to create fear about society endangering the rights and power of White people. The forum below is two of the most recent discussion topics with the first talking about the danger of Jews and the second saying that Whites are under attack by minorities:

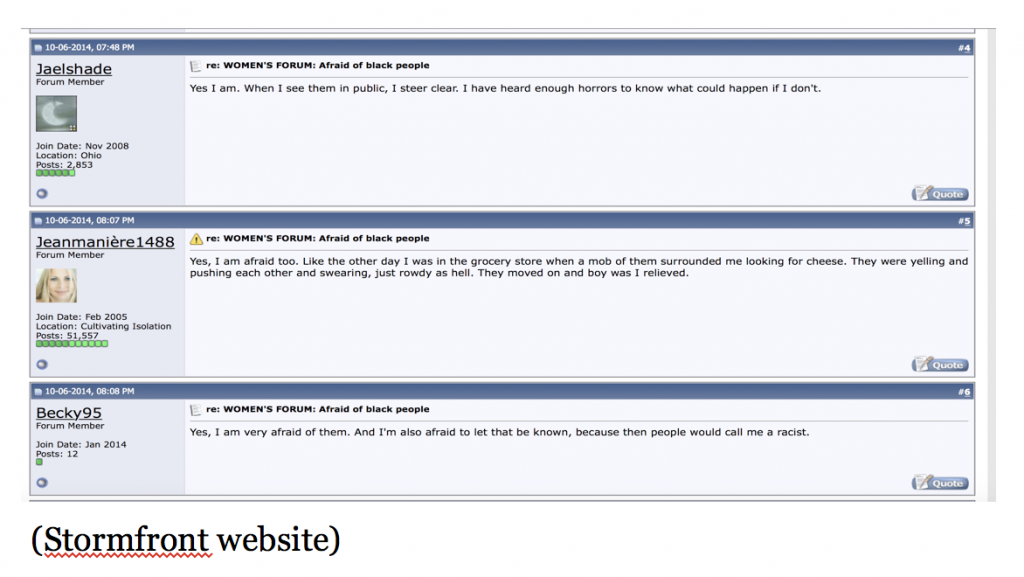

Through these forum posts, the website seeks to reference ‘the other’, relegating “those delegated as non-White to lower and inferior positions in the hierarchy” (Sorrells, 2013, p. 58). The website warns against non-White people who are not as intellectually capable trying to overthrow the dominant power of Whites. They consistently mention other races as incapable of intellectual thought and who are a threat to White supremacy. They encourage hate by characterizing them as harmful to White people with personal anecdotes and by associating certain stereotypes with people of other races. In one forum post, a woman asks her fellow members if they are also afraid of Black people:

The members who responded all agreed that they were afraid of Black people as well. All of the members distinguished Black people as the “other” by using the term “them”. The second woman referred to Black people in a store as a “mob” instead of a group, evidently expressing a negative connotation and assuming they were there to cause problems. The third woman responded by agreeing with the unanimous fear, but also mentioning that she would be afraid to express that openly in fear of being called racist. The author, continuing, states: “I know it isn’t “fair” of the world for Blacks to have to be born with such a disadvantage, but the first rule in wanting to help them is that you don’t become like them” (Stormfront). The website wants to establish the inferiority of other races to promote White supremacy and give others a reason to believe that other races are distinctly different from White people.

Opposing Views

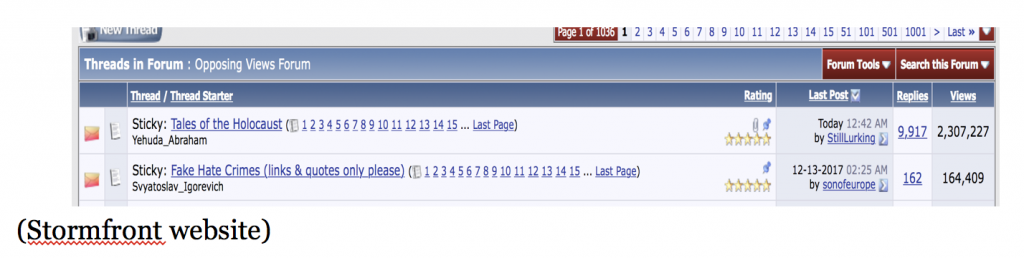

The description under the opposing views forum explains that the website welcomes guests with views who do not align with White supremacy. However, when I entered, it simply tried to take away the credibility of opposing views. For example, there was a link to further prove their point about the Holocaust not existing and another link about stories of fabricated hate crimes to endorse the view that hate crimes are essentially not real:

The forum is misleading because it makes it seem as though others are welcome to oppose White supremacy and challenge their ideals, when in fact it is simply destroying opposing views through sources that are not supported. They used biased articles that are not credible, but give the appearance of looking professional. It seems to justify their point from an outside source; the viewers are not going to check the credibility of every article. In fact, the author of this website could be producing these outside articles. A lack of genuine facts and knowledge can lead to dangerous misinterpretations and stereotypes about people of other races.

Hate Crimes Online

The Internet is being used to promote racist ideas and “because the First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech broadly, the United States government is limited in its ability to regulate online speech through existing civil and criminal law, and governmental attempts to pass new content-based laws regulating online speech by and large have been declared unconstitutional” (Henry, 2009, p. 236). Hate speech online can lead to hate crimes in person as extremists seek support in one another, constantly growing their community’s prejudices. Their speech is fully protected and Americans are left vulnerable as “the reluctance of the Justice Department to take legal action, even when faced with documented harassment and intimidation, is striking” (Henry, 2009, p. 236). With little protection and growing websites online, extremists are able to successfully intimidate their victims, while bolstering their recruiting efforts. The First Amendment was meant to preserve the democratic freedoms afforded to citizens, but a cyber world of hate has evolved, posing a threat to equality in the digital world.

References:

Gerstenfeld, P., Grant, D., & Chiang, C. (2003). Hate online: A content analysis of extremist Internet sites. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 3(1), 29-44. Retrieved from http://spssi.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/journal/10.1111/(ISSN)1530-2415/

Henry, J. (2009). Beyond free speech: novel approaches to hate on the Internet in the United States. Information & Communications Technology Law, 18(2), 235-251. doi: 10.1080/13600830902808127

Posselt, G. (2017). Can hatred speak? On the linguistic dimensions of hate crime. Linguistik online, 82, 5-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.13092/lo.82.3712

Rubinkam, M. (2017, December 2017). Former Berks housing worker once targeted by KKK loses daughter, blames harassment. The Morning Call. Retrieved from http://www.mcall.com/news/nationworld/pennsylvania/mc-pa-harassed-housing-worker-from-berks-20150529-story.html

Sorrells, K. (2013). Intercultural Communication: Globalization and Social Justice. New York, NY: Sage Publications.

Stormfront homepage. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.stormfront.org/forum/index.php

Volokh, E. (2017, June 19). The Slants (and the Redskins) win: The government can’t deny full trademark protection to allegedly racially offensive marks. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/06/19/the-slants-and-the-redskins-win-the-government-cant-deny-full-trademark-protection-to-allegedly-racially-offensive-marks/?utm_term=.a31db099e57a

Volokh, E. (2017, June 19). Supreme Court unanimously reaffirms: There is no ‘hate speech’ exception to the First Amendment. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/06/19/supremecourt unanimously-reaffirms-there-is-no-hate-speech-exception-to-the-first-amendment/?utm_term=.7933ea675d26

[1] Sara Eljouzi is a Communications major. She graduated from Ramapo College of New Jersey in Spring 2018.

Thesis Archives

| 2020 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2014 |Copyright ©2025 Ramapo College Of New Jersey. Statements And Policies. Contact Webmaster.