- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

Alternative Affirmative Action: Evaluating Diversity at Flagship Universities under Race Blind Admissions

(PDF) (DOC) (JPG)January 26, 2016

Elizabeth Bell

Elizabeth Bell majored in Political Science from Southwestern University.

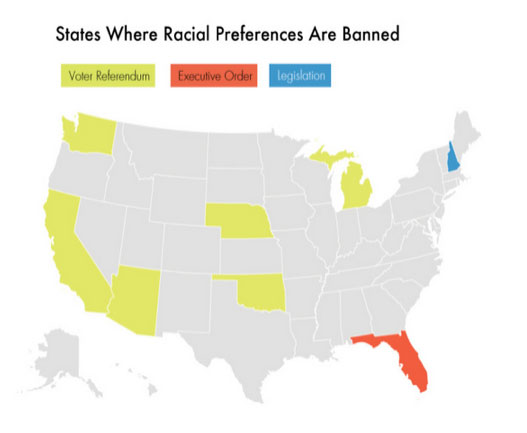

America’s commitment to equality, justice, and fairness has been called into question in affirmative action debates.[1] Even so K-12 schools continue to have racially stratified achievement, and pervasive segregation that prevents students from reaping the benefits of racially and ethnically diverse learning environments. Americans have remained divided, with citizens and social scientists rarely in consensus on how to encourage the enrollment and graduation of students from diverse backgrounds. Eight states have shifted towards alternative affirmative action procedures (Figure 1), where voter referendums, executive orders and legislation have outlawed preferential treatment based on race in university admissions.

Figure 1. Source: The Century Foundation, www.tcf.org

Through a comparative case study of two alternative affirmative action policies, the Texas Top Ten Percent Policy and the One Florida Plan, this paper will assess and compare the resulting diversity of student bodies at the flagship state universities. Additionally, the ethics of these two policies will be evaluated based on the principles presented by Virginia Held. According to this investigation, both the Texas Top Ten Percent Policy and the One Florida Plan have not increased the attendance of racial and ethnic minorities at state flagship universities in Texas and Florida, as originally intended. However, innovative strategies at the university level have been implemented to attract diverse groups of students by providing economic and educational support to those who face systemic disadvantage in the midst of “race-blind” admissions. These university policies have the potential to guide future policymakers in admitting racially diverse students without having to consider race as a factor in college admissions.

Historical context

Affirmative action debates began with Franklin D. Roosevelt advocating legislation like the 1933 Unemployment Relief Act, which stated that “no discrimination shall be made on account of race, color, or creed” (Anderson, 2004, p. 11). During the civil rights movement these programs expanded to include granting minorities preferential treatment in employment and educational opportunities to account for historical discrimination and exclusion, which “many whites and conservative allies” considered “reverse discrimination and unfair” (Anderson, 2004, p. 76-97). This rhetoric is echoed by contemporary conservatives in the movement to champion meritocracy as an alternative to affirmative action. However, as the Johnson administration found, in the era of segregated schools, preferential treatment was necessary because “if businesses continued to hire the most skilled person for a job, it would almost always be white applicants” (Anderson, 2004, p. 97).

As a result of these political disagreements, many citizens have pursued litigation for more clarity on the constitutionality of affirmative action policies. In the University of California v. Bakke case in 1978, the Supreme Court found that “racial diversity serves a compelling state interest, allowing public institutions to count race as one of many diversity factors for admission” under strict scrutiny standards established by the court (Lloyd, Leicht and Sullivan, 2008, p. 1). Strict scrutiny is the assessment the court applies to cases in which a universities’ consideration of race as a factor has been challenged. Affirmative action programs meet strict scrutiny if the consideration of race is “narrowly tailored to achieve the only interest that this Court has approved: the benefits of a student body diversity that encompasses a broad array of qualifications and characteristics of which racial or ethnic origin is but a single though important element” (Lloyd, Leicht and Sullivan, 2008, p. 1).

However, in the 1996 Hopwood decision in the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court the use of race in college admissions was outlawed. In Gratz v. Bollinger the Supreme Court found that the University of Michigan undergraduate college program was not narrowly tailored in the use of race in admissions. Nonetheless, in Grutter v. Bollinger the Supreme Court found that another University of Michigan program was narrowly tailored enough to meet strict scrutiny standards. More recently, in Fisher v. The University of Texas at Austin the Supreme Court sent the case back to the lower court to avoid making a decision until they gather all the necessary information on the admissions program. In response to the conflicting rulings, universities and state lawmakers have adjusted admissions procedures accordingly, in order to avoid litigation.

For example, as a result of the 1996 Hopwood decision, which outlawed the use of race in college admissions in Texas, the state legislature instituted the Top 10% Plan, which guarantees students ranking in the top 10-percent of their high school class admission to any state universities along with increased financial aid. The law also specified the eighteen factors, which should be considered for students not automatically admitted: “family income, parents’ level of education, first generation college status, and financial and academic record of the student’s school district” (Kahlenberg, 2014, p. 27). At the University of Texas at Austin (UT) these consideration factors became known as the Personal Achievement Index, as opposed to the Academic Index (which emphasized standardized tests and GPA) prior to Hopwood. The personal achievement index was created in order to encourage a more diverse class, because of the disadvantages students with less resources face in standardized tests (Lavergne and Walker, 2002).

Following the footsteps of Texas, Florida enacted its own alternative affirmative action to include socio-economic factors instead of race. Governor Jeb Bush announced Executive Order 99-281, or the “One Florida Plan” including the Talented 20 plan, which guarantees students ranking in the top 20-percent of the graduating class that also submitted ACT or SAT scores admission to the State University System, “though not necessarily to their school of choice” (Kahlenberg, 2014, p. 50). In addition, the One Florida Plan banned the consideration of race, ethnicity, and gender while allowing factors such as “family education background, socioeconomic status, graduate of a low performing high school, geographic location and special talents” to be considered (Kahlenberg, 2014, p. 50). Furthermore, the One Florida plan increased access to financial aid programs for first-generation students and for the students eligible for the Talented 20 program. However, even after a decade of implementation it remains unclear whether these laws have improved racial and ethnic diversity, which will be assessed in this study.

Ethical theory

Since public policy is grounded in the pursuit of a more ethically responsible society, the laws will be examined through the lens of Virginia Held’s political theory of care. The Ethics of Care has five central components:

- “The compelling moral salience of attending to and meeting the needs of the particular other for whom we take responsibility,”

- The “conception of persons as relational, rather than as the self-sufficient independent individuals of the dominant moral theories,”

- A restructuring of the personal (private) and the political (public) realms,

- A celebration of emotion, and

- A de-emphasis on abstractions” (Held, 2007, p. 10-13).

Whereas Kant and Mill consider citizens as independent, rational beings, Held highlights the importance of caring relations between citizens in the foundation of her theory. Held argues that the morality of dependence is fundamentally human, which has been overlooked by moral theorists such as Kant and Mill who hold that “moralities (are) built on the image of the independent, autonomous, rational individual” (Held, 2007, p. 10). This relational view of society is essential to the discussion of affirmative action because in many ways affirmative action is the way in which we care for those whose systemic disadvantage we take responsibility for (racism, slavery, Jim Crow, segregation, sexism, classism etc.). These instances of care require not only human reason, but also human emotion. The rational, independent, enlightened self-interest helps preserve fairness, while the compassionate, emotional, relational component insures the preservation of life, success and happiness. In order for society to fulfill its potential or telos, there must be an element of care along with a moral minimum of justice and fairness. In this way we strive toward Held’s normative civil society in which “the needs of every child would be a major goal, and doing so would be seen to require social arrangements offering the kinds of economic and educational” support that ensures the mutual consideration of other people as citizens with value (no matter their test scores or the amount of money their parents make) (2007, p. 136).

Instead of the classical view, where justice is the ultimate goal in society with the role of care as a peripheral component, Held argues that justice and care are intertwined, not mutually exclusive. Held argues that “there can be care without justice” but “there can be no justice without care, for without care no child would survive and there would be no persons to respect” (2007, p. 17). Furthermore, she argues that care as a practice “shows us how to respond to needs and why we should. It builds trust and mutual concern and connectedness between persons” (Held, 2007, p. 42). In the case of affirmative action, the ethics of care would advocate responding to disadvantaged and excluded populations by providing accommodations for these students that help build back the trust that some students lose in the university system. For example, to accommodate racial and ethnic minority and low-income students, universities can pursue outreach, scholarship programs and expanded financial aid that increase confidence and trust in our university system.

In the South, Black and Latino students together comprise more than 90 percent of the student population in extreme poverty schools (Orfield and Lee, 2005, p. 27). Additionally, 87-percent of the average black student’s peers are black, revealing the extreme isolation of high poverty and majority black schools in the South (Orfield and Lee, 2005, p. 27). In Texas, bachelor’s degree attainment remains stratified by race with 33-percent of white students graduating with a bachelor’s degree, while only 17-percent of black students and 10-percent of Hispanic students graduating with a bachelor’s degree (Creusere et al, 2015). According to Education Secretary Arne Duncan, “in 20 states, the districts with the highest percentage of minority students spend fewer state and local dollars than in districts with the lowest percentage of minority students… And sadly, over the last decade, this divide—this inequity – has only gotten worse. Since 2002, the gap between per pupil expenditures in high and low poverty school districts has actually grown wider – from a gap of 10.8 percent to a gap now of 15.6 percent” (U.S. Department of Education, 2015). In Florida, severely segregated schools are considered institutions of concentrated disadvantage and policies “that attempt to resolve the achievement gap by funding equity or classroom size changes” would probably fail if the segregation issue were not addressed (Orfield and Lee, 2005, p. 27).

Despite the inequities, critics of affirmative action consider preferential treatment in admission as increasing negative stereotyping and eroding perception of minority students’ competence. Instead of considering race in admissions, opponents suggest that affirmative action programs should be focused on enhancing performance of historically underrepresented groups while retaining standard evaluations (which could be interpreted as standardized tests). In this way, policies would demonstrate the success of minorities in leadership positions that they were able to acquire through dedication and work ethic (Anderson, 2004, p. 343).[2] This argument is problematic considering the flawed underlying assumption that “those who develop the tests and measures, as well as those who implement them, are fair and unbiased” (Crosby, 2004, p. 58-59). While it would be ideal to provide a free market in which students could compete based on standard evaluations, this neglects the inequality that is evident and perpetuated by our flawed K-12 education system.

Additionally, the prevailing inequality would perpetuate negative stereotypes about the competence of racial minorities more than the consideration of race as one of the many factors in college admissions. Stratified achievement and segregation are both concepts that students come in contact with every day, and it seems that these inequities have the potential to increase negative stereotypes of racial minorities more significantly than the consideration of race as one among many factors in admissions. Race as a factor in admissions under strict scrutiny standards involves personalized assessment with a multiplicity of factors that assess a student’s viability, which works to provide more opportunities for disadvantaged groups despite what might be considered their “market value.”

Held celebrates the ability of care to tame problematic market forces. For example, the University of Phoenix—a profit making institution aiming to have 200,000 students, with uniform class syllabi, almost no full-time teachers, and lots of online learning—may well by the higher education of the future. Here we can see the values of the market: the way the worth of value of an activity or product should be ascertained is by seeing the price it can command in the marketplace; those whose work is not rewarded with profits are not doing work that has worth; efficient management and high productivity take priority over, for instance, independent thought or social responsibility (Held, 2007, p. 115).

Held argues that once educational institutions are taken over by the values of the market, “anything other than economic gain cannot be its highest priority, since a corporation’s responsibility to its shareholders requires it to try to maximize economic gain” (Held, 2007, p. 115). In this way, Held argues that we “put economic gain ahead of devotion to knowledge” (Held, 2007, p. 116). Some scholars advocate competition based on standardized tests as a healthy and reasonable way of demonstrating acquired knowledge. On the contrary, Held argues that our schools should not be competing based on test scores, because these are ways for market forces and corporations to subordinate schools to the demands of the market which necessarily impedes “the function that culture needs to perform to keep society healthy, the function of critical evaluation, of imagining alternatives not within the market, of providing the citizens the information and evaluations they need to act effectively as citizens” (Held, 2007, p. 123). In practice, the Texas Top Ten percent law curbed the influence of standardized tests, which disadvantage students with less resources, exemplifying the ethics of care in its ability to consider more pertinent factors such as how well the student could do with the limited resources available to them. However, the One Florida Plan incorporated standardized tests as a necessary component for automatic admission to the State University System. No doubt the partnership with College Board, which administers the SAT, played a role in this measure.

Unlike the values of the market, “the values of shared enjoyment or social responsibility, or collective caring” are evident in the efforts on the part of universities to diversify and accommodate disadvantaged students (Held, 2007, p. 118). When political scientists study diversity on campus, they are studying the practice of care between students of diverse backgrounds. The campus cares for diverse groups of students by providing safe places to interact, and a diverse student body whose differences foster connections between persons of all races, religions, political leanings, and socio-economic statuses. An ethical university should be structured to meet the needs of students no matter their socio-economic, racial, or religious background. This is the way to reach equality of opportunity in higher education, and affirmative action policies that seek to partner with low-income schools and provide extra support to disadvantaged students may well be an integral component of caring for underrepresented populations. Currently, the alternative affirmative action programs in Texas and Florida may seek to provide equal opportunity by admitting students from disadvantaged high schools, but it is unclear whether these initiatives are improving racial and ethnic diversity, as originally intended.

Method

The most-similar comparative case study methodology will be utilized to evaluate and compare the One Florida plan and the Texas Top 10% law. The most-similar comparative case study is useful because while both of the laws incorporate a measure that guarantees a certain percentage of top ranking high school students’ admission to state universities, the Florida initiative incorporates measures to improve the performance of underprivileged students before entering college. The percent plans are relatively similar, which will provide analytical leverage for the other provisions and university level policies that make the plans different.

The independent variable is the policy implementation of race neutral affirmative action procedures of the Top 10% law at the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University and the implementation of the One Florida Plan at the University of Florida. Given the limited scope and resources available, these flagship state universities should provide a lens into the diversity of college campuses in the two states. The similarities and differences within the policies will aid in understanding possible explanations for the higher or lower enrollment results of racial and ethnic minority students. Thus, the dependent variable is the admission rates of racial and ethnic minorities a couple years before the measures were passed compared to the current admission rates. This variable will be evaluated based on the common data set statistics at each university, and whichever law (or university implementation procedures) has had the most consistent success in admissions of racial and ethnic minorities will be considered the more “successful” plan in adhering to the ethics of care.

Top Ten Percent Plan

On a statewide level, the Texas Top Ten percent law was coupled with The Towards Excellence, Access and Success (TEXAS) Grant in 1999 and the Top 10 Percent Scholarship Program in 1997 to increase financial aid and indirectly encourage more racial diversity following the ban on racial preferences post-Hopwood. At the university level, the implementation of the Top Ten percent law at the University of Texas (UT) differs from the implementation at Texas A&M University (A&M) based on the relevant court cases and respective university response. For instance, as a result of Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), UT “reopened the possibility of using racial/ethnic preferences in admissions” while A&M “chose not to reinstate racial preferences after the Grutter ruling but continued aggressive outreach, recruitment, and scholarships to promote diversity” (Kahlenberg, 2014, p.31). Following the ban, UT implemented recruitment programs for underrepresented geographic areas and K-12 partnerships including UT Outreach, which provides “test prep, application help and financial aid advice” (Kahlenberg, 2014, p.33). Additionally, in response to the backlash from minority students and parents, A&M stopped granting preferential treatment to legacy students after announcing the continuance of their race-blind admissions standards (Kahlenberg, 2014, p.27). Both UT and A&M have developed scholarship programs such as the Longhorn and Century Scholarships that “enabled economically disadvantaged top 10% graduates to attend their institutions” (Harris and Tienda, p. 15-17). Based on the relevant research and available data on racial and ethnic diversity at UT and A&M, it seems that University level implementation had more success in encouraging the enrollment of minorities than the implementation of the Top Ten percent law.

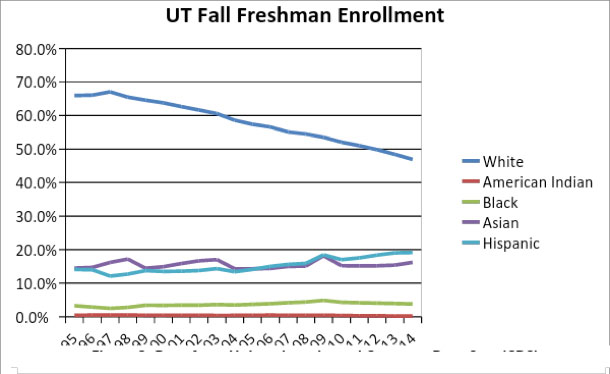

Figure 2. Source: University of Texas at Austin.

Data analysis of admissions suggests that the racial diversity at UT increased more significantly than A&M, especially after the reinstatement of the use of race in applications. As we can see in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the first class admitted after the University of Texas at Austin stopped using race as an admissions factor had fewer minorities. However, once the university began implementing programs to reach out to prospective students at schools with more racial diversity there was an increase in admission shown by the years 2001-2010. Hispanic enrollment increased from 15-percent to 19-percent, and Black enrollment fluctuated between years never increasing by more than 1-percent.

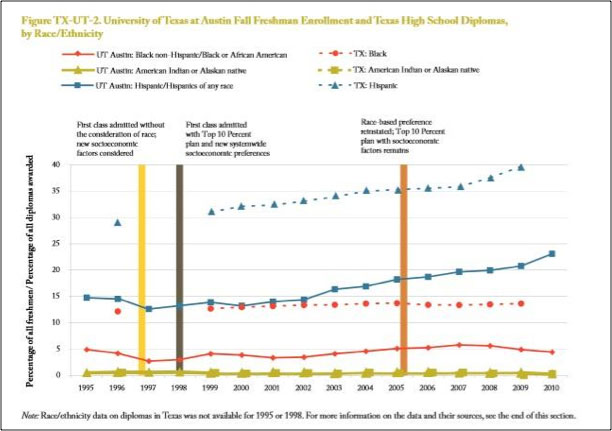

In order to account for fluctuations in the population, Figure 3 compares the percentage of racial minorities graduating from high school and the percentage of that minority represented at UT.

Figure 3. Source: Kahlenberg, 2012, p. 30.

As shown in Figure 3, despite the best efforts on the part of universities, “the new policy created a student body that was increasingly disproportionate to the demographics of the State of Texas” (Charleston, 2009, p. 14). The dotted line represents the percentage of Black, Hispanic or American Indian students in Texas that graduated from high school eligible for college and the solid line represents the enrollment percentage of that race or ethnicity at UT. Clearly, the disproportionate underrepresentation of Hispanic and Black students exists, however it seems that when UT incorporated race as a factor the gap between these two measurements slowly starts to decline by a couple (1-3) percentage points. This improvement is not evident at A&M.

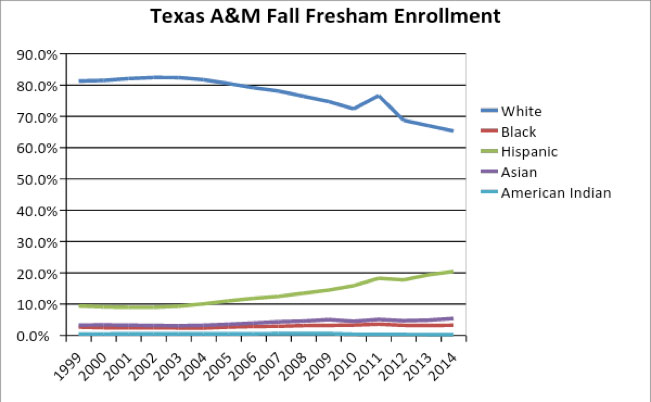

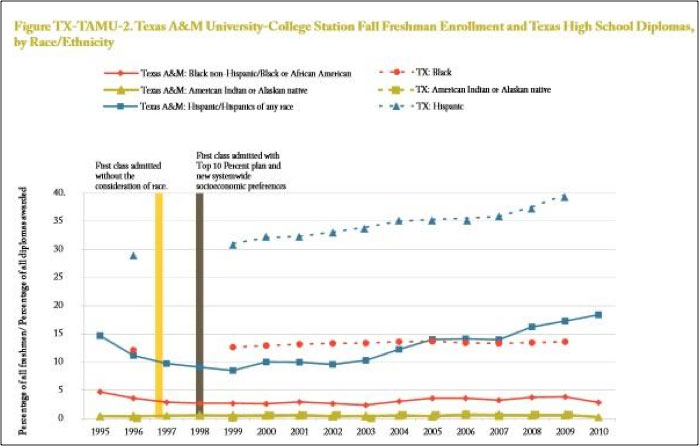

Racial diversity at Texas A&M seems to be even more stagnant than UT’s enrollment, as shown in Figure 4. Additionally, while it seems as though there is an increase in Latino/Hispanic enrollment after 2010, this can actually be attributed to the Department of Education changing racial classifications. After 2010, the demographic “Hispanic” was grouped with multiple other racial categories including mixed race and those identifying as “Latino”, which creates a confounding variable in the comparison of the enrollment over time. The data would seem to highlight an increase in Hispanic enrollment, however even after the reporting changes the student body at Texas A&M does not accurately reflect the amount of racially diverse students who acquire a high school diploma, shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4. Source: Data from University released Common Data Sets (CDS)

The gap between Hispanic and Black students who graduate with a high school diploma and the proportion of those demographics present in the student bodies of Texas A&M hasn’t improved since the inception of the Top Ten Percent law. Additionally, it seems that before the implementation of the percent law, the gap between Hispanic students graduating from high school and the proportion represented at A&M was around 18-percent, while this gap remains at a constant 20-percent after the implementation of the Top Ten Percent Law.

Figure 5. Source: Kahlenberg, 2012, p. 32.

Many experts respond to stagnating racial diversity at Texas flagship universities by arguing that “by itself, the 10 percent plan will not adequately diversify campuses” (Tienda et. al., 2003, p. 2). For instance, Harris and Tienda utilize administrative data on applicants and enrollment of Hispanic students to evaluate the effects of the Top Ten percent law on this demographic. After examining UT and Texas A&M University before and after the Top Ten percent law was in effect, the authors conclude that “Hispanics are more disadvantaged relative to whites under the top ten percent admission regime at both UT and TAMU” because the average “percent of Hispanic applicants admitted to UT-Austin and TAMU was lowest after the enactment of the top 10% law” (Harris and Tienda, 2012, p. 1-9). Before the implementation of the Top Ten percent law, “Hispanics enjoyed an admission advantage relative to whites under affirmative action (3.2 and 12.2 percent points at UT and TAMU, respectively), but faced lower admission prospects compared with whites under both alternative admission regimes” (9). While scholars and citizens agree on the noble ends of affirmative action in encouraging achievement among underrepresented groups, some scholars would consider using means in which Hispanics are advantaged regardless of socioeconomic status and other admissions factors as not the most ideal implementation (Kahlenberg, 2012). In response to this argument, Harris and Tienda propose that “simulations of Hispanics’ gains and losses at each stage of the college pipeline across admission regimes confirms that affirmative action is the most efficient policy to diversify college campuses, even in highly segregated states like Texas” (Harris and Tienda, 2012, p.1).

In their explanations for why enrollments haven’t increased for minority students, other scholars argue that the Top Ten percent plan was not a significant shift in university policy. Chapa argues that “the automatic admission of any applicant in the Top 10% of his or her high school class was standard practice,” even at the University of Texas at Austin, before the top ten percent law was initiated (Chapa, 2005, p. 189). This is a substantial finding that is echoed by many other researchers on the Top Ten percent plan, which suggests that the implementation of the plan did little to change the system already in place for university admissions (Tienda et. al., 2003; Harris and Tienda, 2012; Charleston, 2009). It should also be noted that authors attribute “UT’s success in recruiting more minorities under HB 588” to “its vigorous recruitment efforts as well as restricted financial aid programs” not the implementation of the Top Ten percent law (Walker, 2000). This is another confounding variable in the studies that examine enrollment rates without looking at the universities policies that were implemented to make up for the possibility of decreasing enrollment of disadvantaged students. This finding suggests that university level implementation, not the Texas Top Ten Percent law provided an alternative approach to affirmative action solely based on the consideration of race.

However, not every university is willing or able to implement programs that encourage racial diversity. The difference between UT racial diversity and Texas A&M racial diversity highlights a successful reinstatement of the use of race supposedly under the strict scrutiny standards established by the court, along with the socio-economic factors in the Personal Achievement Index. These small differences in the admission process at UT could provide Held’s system of care to account for prevailing racial inequity, while also adhering to the standards of justice by only considering race under strict scrutiny standards.

In my analysis of the literature in favor of the Texas Top Ten percent law, I found that authors often overlook essential variables such as the average enrollment rates of racial minorities over time. For instance, in response to the concern that “underrepresented communities do not have confidence in the openness and integrity of the educational systems and further, are often unable to access high-quality education and training without affirmative action” (Dudley-Jenkins and Moses, 2014, p. 94), some researchers argue that the Top Ten percent law has improved disadvantaged students’ college aspirations. In a random sample of Texas senior public high school students, researchers found through statistical analysis that knowledge of the percent plan increased the number of racial minority students considering going to college (Lloyd, Leicht and Sullivan, 2008). While this data may seem to highlight a benefit of the percent plan, an increase in college aspirations cannot address the entire implementation of the percent plan because the authors overlook essential variables such as enrollment rates.

Many low-income first-generation and minority students face obstacles to enrollment even though they have college aspirations, which some school districts in Texas are trying to address through the innovative Summer MELT program.[†] Unless the data on enrollment shows an increase in underprivileged students, the Top Ten Percent plan should not be touted as a successful alternative to affirmative action. However, other researchers do confirm that “the fall 2002 freshman class at the University of Texas had many more top 10% minority students and more African American and Latino students than the last class admitted using race-conscious affirmative action” (Lavergne and Walker, 2004), while the “Texas A&M’s freshman class in the fall of 1999 had far fewer minorities then was the case before Hopwood” (Chapa, 2005, p. 190). While the increase in student representation during this time period for the University of Texas is notable, the authors neglect to compare the enrollment rates to the average percentage of minorities during the period following the reinstatement of race-conscious affirmative action and instead look at a single year’s data. Each year is going to fluctuate, and it is important that researchers of affirmative action look at the trends between multiple years to get a more accurate picture of the real outcomes of the policy.

In another study done by the Higher Education Opportunity Project, researchers highlight that while “universities changed the weights they placed on applicant characteristics aside from race and ethnicity in ways that aided underrepresented minority applicants, these changes in the admissions process were insufficient to fully restore black and Hispanic applicants’ share of admitted students” (Long and Tienda, 2010). Furthermore, Charleston employs a comparative case study methodology in his research, arguing that “because anti-affirmative action legislation has damaged efforts to increase diversity within higher education” as shown by the prevailing racial disparity relative to the population, “state systems will have to be more systematic regarding state efforts to attract, admit, and matriculate students who have historically maintained under-representation relative to their share in the population” (Charleston, 2009, p. 14). Additionally, while certain universities are willing to devote the time and resources to these systematic efforts not all universities may have equal success in implementation (as shown by TAMU), which creates further inequality across state university systems.

In response to the accusation that the Top Ten Percent law admits unprepared students who are forced to drop out, researchers have investigated how students from lower-income high schools are doing at the selective colleges they can now receive automatic admission to. After observing the grade point averages and retention rates of students who would not have been admitted to the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University before the Top Ten percent law, Tienda and Niu argue that many students from low-performing Texas high schools (even students with SAT scores under 900) are doing quite well (Tienda and Niu, 2006, p. 190-191). However, Furstenberg argues that the students who would not have been able to enroll in a selective college without the Top Ten percent plan have lower GPAs and lower probability of graduation (Furstenberg). The difference between these studies is that Tienda and Niu consider doing well as being in good standing with the university, while Furstenberg compares students from lower-performing high schools to all students’ GPAs at the universities. Both studies employ similar methods (statistical analysis), but Tienda and Niu account for the vastly unequal K-12 education system in Texas while Furstenberg doesn’t control for this variable. In this way, Tienda and Niu’s findings seem more compelling even though they are counterintuitive. The fact that students with significantly lower SAT scores are able to stay in college with good standing should be evidence suggesting that the Top Ten percent law’s deviation from considering standardized test scores in admissions of students in the top of their high school class as effective, and justified under the ethics of care.

The movement away from a reliance on standardized test scores is also encouraged by Sigal Alon and Marta Tienda (Alon and Tienda, 2007). The authors argue that before we evaluate how well our new systems are working for disadvantaged students we must first realize why we identify groups of disadvantaged students in the first place. One of the ways our system disproportionately disadvantages students is through “the emphasis on test scores in college admissions” which “notably benefits those with more resources,” causing “selective institutions to give underrepresented minorities an admissions boost to achieve campus diversity” (Alon and Tienda, 2007, p. 507). However, at many universities standardized test scores continue to be emphasized despite “mounting evidence that test scores have low predictive validity for future academic success, particularly when compared with performance-based measures like grades or class rank” (p.507). Here we see the values of the market, where the motivations for selective institutions to “climb the pecking order in various college ranking systems” overpowers the need to create a system in which all have the opportunity to succeed (p.508). The use of standardized tests is not advocated by Held, but as long as other factors are given equal weight, including socio-economic factors, the disadvantages students face could be addressed. However, these tests are also sometimes used to establish merit scholarships, which further disadvantage those with less financial resources who do not have the luxury of taking costly test prep courses.

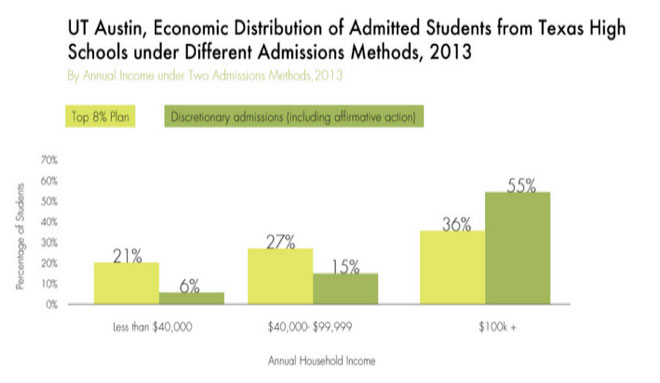

My initial intent was to examine the socio-economic diversity before and after these laws, but the data for the Fall Freshman student bodies separated by family income is not provided in the Common Data Sets published on the university webpage. Currently, universities are only required to release statistics on the racial composition of their incoming freshman classes but socio-economic status can be excluded. As a result, there is less literature on this topic and less data analysis readily available. However, as we can see in Figure 6, researchers have found that there is more socio-economic diversity under the Top Ten percent law. In the 2010-2011 school year there was close to 27-percent of the incoming class receiving Pell Grants, while only 18-percent were Pell Grant recipients from 1994-1999 (Kahlenberg, 2014, p. 35).[3] Therefore, under the Ten percent law university level policies played a large role in helping more economically disadvantaged students, but this still does not solve the issue of racial and ethnic diversity.

Figure 6. Source: Kahlenberg, 2014, http://apps.tcf.org/future-of-affirmative-action.

Kahlenberg highlights that low-income students are the most underrepresented population at the university level, which provides justification for utilizing economic affirmative action. For instance, “in a 2013 report, Anthony Carnevale and Jeff Strohl noted that while white students are overrepresented at selective colleges by 15 percentage points, the overrepresentation of high-income students is 45 percentage points, three times greater” (Kahlenberg, 2014, p. 3). He argues that because “wealth is accumulated over generations, the nation’s steep wealth inequality reflects in some important measure the legacy of slavery and segregation as well as ongoing discrimination in the housing market” but that “smartly structured economic affirmative action programs can address the instances of discrimination indirectly, without conflicting with our legal system and public perceptions of fairness” (Kahlenberg, 2014, p. 24).

As a result of the stagnant, yet consistent percentage of racial minority students after the implementation of the Top Ten Percent law, Kahlenberg argues that “it is possible to produce a critical mass of African American students in leading universities without resorting to racial preferences” (Kahlenberg, 2014, p. 17). However, it should be clear that in the university implementation racial preferences are included although not explicitly. Kahlenberg himself agrees that university level implementation of alternative affirmative action procedures have been a determining factor in the admission of racially diverse student bodies under the percent plan. Kahlenberg highlights:

Universities … have spent money to create new partnerships with disadvantaged schools to improve the pipeline of low-income and minority students. They have provided new admissions preferences to low-income and working-class students of all races. They have expanded financial aid budgets to support the needs of economically disadvantaged students. They have dropped legacy preferences for the generally privileged—and disproportionately white—children of alumni. They have admitted, irrespective of test scores, hard-working students who graduated at the top of their high school classes, thereby granting access to students from low-income schools that had little history of sending graduates to selective colleges when racial affirmative action was in place (Kahlenberg, 2014, p. 1).

These changes in university policy are inherently race-conscious, and while these strategies have been adopted at some universities it should be noted that Kahlenberg utilized a comparative case study methodology in which many different states were analyzed. In no way does this mean that all of these efforts have been put in place by all colleges affected by bans on race based affirmative action, but Kahlenberg’s research does show that these efforts listed above do enable colleges and universities to obtain the diverse student bodies in a new way.

However, he also argues that it is unrealistic to use race-based and class-based affirmative action simultaneously. This is problematic because UT considers both race and socio-economic status and is touted as the most successful implementation of these programs in his study. As Gaertner and Hart argue, there is no other factor that can serve as a proxy for race, which is why UT has been able to obtain both socio-economic and racial diversity simultaneously (Gaertner and Hart, 2013, p. 15). While they agree with Kahlenberg that socio-economic affirmative action needs to be pursued, they also note that “the failures of these class-based approaches to achieve desired levels of racial diversity seem to vindicate the nearly unanimous conclusions of prominent affirmative action researchers that “the correlation between income and race is not nearly high enough that one can simply serve as a proxy for the other” (Gaertner and Hart, 2013, p. 15).[4] Therefore, if universities resorted to only employing economic affirmative action, the racial diversity at the University would not be ensured, as seen in the stagnant racial diversity at Texas A&M University.

Finally, research suggests that racial minorities not in the top ten percent of their high school class have significantly lower enrollment, retention and graduation rates after the implementation of the Top Ten percent plan (Cortes, 2010). The author highlights how after the elimination of race as a consideration in admissions, there was an increase in the graduation gap between minorities and non-minority students in Texas. Other researchers confirmed these findings in their regression discontinuity approach, which found “no evidence of effects on college choice in the schools with the lowest college-sending rates” (Daugherty, Martorell, and McFarlin, 2012, p. 21). So not only does the Top Ten percent fail in increasing access to higher education for the high schools that need it most, it also could be contributing to crowding out underrepresented groups not eligible for the automatic admission from attending the state flagship universities.

Based on the enrollment rates at UT and Texas A&M, and the relevant research explored in this section it seems the Texas Top Ten Percent law has not improved the racial and ethnic diversity at state flagships, but that innovations at the university level have the potential to fundamentally alter the way programs are tailored to consider race as a factor. Partnerships with historically excluded high schools, expanded financial aid programs including scholarships targeting low-income students and an emphasis on outreach and recruitment all have the potential to revitalize a supportive and attentive university structure. Additionally, it seems that considering race as an admissions factor helps universities acquire racial and ethnic diversity based on the higher enrollment rates at UT compared to those at A&M. These programs work toward fulfilling Held’s normative ethical theory, in which a broad compassionate system of care reestablishes trust and respect between all different types of citizens.

One Florida Plan

The One Florida Plan has been met with equal, if not more, skepticism by scholars because of the preemptive actions taken by Governor Jeb Bush to ban affirmative action based on race before the measure was placed on the ballot for citizens to vote on. As Charleston highlights, “when Ward Connerly[‡] took his campaign to end affirmative action to Florida in 1999,” the Governor “requested a review of Florida’s affirmative action plans in an effort to assess the legal viabilities thereof. Though he publicly opposed Connerly’s initiatives, deeming them divisive, he voluntarily initiated the One Florida Plan” (Charleston, 2009, p. 14).

Supporters of the law tout the Talented 20 Program and the increased financial aid as a way to increase educational access for underrepresented populations while opponents argue that these efforts have not been successful in encouraging the enrollment of disadvantaged students. The percent plan was paired with “significantly increased funding for need-based financial aid” as well as “a partnership between Florida and the College Board to improve college readiness” by increasing “the number of students, particularly low-income and minority students, enrolling in and passing Advanced Placement (AP) classes” (National Conference of State Legislatures). Succinctly, the initiative puts forth programs specifically targeting low-income schools with large minority populations by increasing the accessibility of college curriculum and providing teacher compensation for teaching advanced placement courses at low performing schools. In effect, the program is intended to provide the students who need it most with the help they need in order to get to college. This is a stark difference between the Texas law and the Florida plan, because while Texas focused solely on college enrollment and partially on financial aid, the executive order in Florida specifically targeted the inequity in K-12 schools that creates the problem of not having socio-economic and racial diversity at the university level. However, as K-12 education reformers have observed, change moves slow throughout these statewide initiatives, which creates a dilemma for the universities now unable to utilize race as an admissions factor.

As a further justification for this plan, the Governor’s office states that “some schools are more equal than others” with high-performing schools offering “tougher curriculums, more experienced teachers, and better opportunities” and that “not surprisingly, the large majority of students attending these low-performing schools are minority students from impoverished families” (The State of Florida Governor’s Office). In this way, the state was attempting to take responsibility for those whose disadvantage Florida institutions have perpetuated and historically caused, which exemplifies the ethics of care. In order to diminish this inequity, the plan hopes that with the “43% increase in need-based financial aid” that the “cost of tuition need not be a barrier to a higher education for those low-income students who show an effort and desire” (p.15).[5] Now, more than ever the One Florida plan needs to be evaluated in light of the experiences in other states as to what does and does not improve the educational success of underrepresented populations.

The central component of the One Florida Plan is The Talented 20 Program, intended to enhance the diversity of the state university system (SUS) by admitting high performing underrepresented student populations who might otherwise not be eligible for admissions. However, researchers highlight that this program is not increasing the admission of underrepresented populations. In fact, in Kahlenberg’s comparative case study, he finds that “only 30 of 16,047 had the possibility of being affected by Talented 20” meaning that students affected by the program would have gotten into college without the help of this program (Kahlenberg, 2012, p. 50). This finding is confirmed by researchers claiming that the Talented 20 plan was largely inconsequential for underrepresented populations based on enrollment rates at Florida’s flagship universities (Lee and Marin, 2003, p. 37; Charleston, 2009, p. 21; Horn and Flores, 2003, p. 9). Charleston explains how “the reactive measures taken by California, Florida, and Texas proved ineffective as the idea of “percent systems” usually encompass those students already on target to qualify for the state institutions’ admission standards” (Charleston, 2009, p. 21).

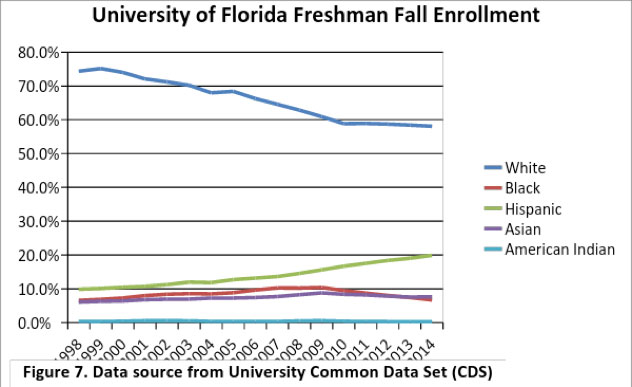

In addition, my data analysis confirms that this law did not consistently increase the racial diversity at the University of Florida shown in Figure 7. Over time, the enrollment of Black students increased to 10-percent in 2006 up from 5-percent in 1998, but declines back to 6-percent by 2014. While it is impossible to determine which specific factors contributed to this fluctuation, surely the financial crisis in 2008 played a role. More importantly, the racial minority that appears to have increased since the law’s implementation can be explained by reporting changes from the Department of Education in 2010. The University of Florida grouped multiple ethnic groups including mixed race individuals in the Hispanic/Latino category, which increased the enrollment numbers of this demographic after 2010. Therefore, “post-2010 data can’t be fairly compared to pre-2010 data” and the reason for enrollment changes is speculated to be because “there are more K-12 students in the state than there were in 1999” and “because of the Bright Futures program” (Gillin, 2015).

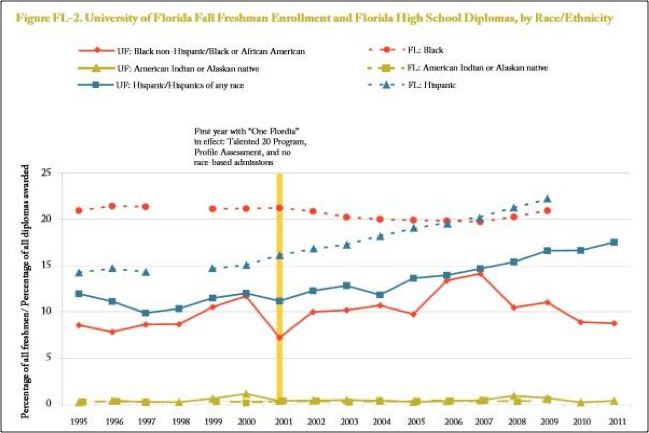

According to Figure 8, the speculation above proves correct. Even though there are more Hispanic students graduating from high school, Hispanic students have

become more underrepresented in the student body of the University of Florida after the implementation of the One Florida executive order. Additionally, Black enrollment was lowest the year One Florida plan was initiated, and the percentage of Black students graduating from high school has declined after the implementation of the One Florida plan. Based on these findings it seems that even after a decade of implementation and after the university was able to incorporate preferential treatment to disadvantaged groups in other admissions processes like financial aid and outreach, the enrollment rates have stagnated relative to the diverse population of Florida.

Figure 8. Source: Kahlenberg, 2012.

Furthermore, in their comparative case study analysis, Horn and Flores highlight how merely admitting students is not sufficient to address the “forces that tend to keep institutions segregated” (Horn and Flores, 2003, p. 8). In fact, if a “disadvantaged minority student is admitted but cannot afford to attend, or believes s/he will be treated badly on campus, the decision to admit may mean little” therefore, admission should be considered a necessary but not sufficient condition for accomplishing the goals of affirmative action (p.9). This is a defining difference between the Texas Top Ten percent law and the One Florida plan. While the One Florida plan emphasized increasing equity among K-12 pipelines and increasing financial aid, the Texas Top Ten percent plan did not do much other than guaranteeing admission. Additionally, this finding emphasizes a major issue that is not addressed in this study, which should be investigated by future researchers. Graduation rates of racial and ethnic minorities at these state flagships would also provide a lens into how well the university is supporting underrepresented groups.

Additionally, the authors explain that “outreach and aid programs that target minority communities… double or triple applications from minority students” which is why when universities claim they have ended affirmative action, they are really pursuing race attentive policies on other fronts (p.9). The efforts are consistent at the university level as a result of both the One Florida plan and the Texas Top Ten percent plan, but not all universities put the same amount of time and resources into these targeted programs. Finally, Horn and Flores (2003) conclude that while “these other forms of race-conscious affirmative action under the right conditions can help some campuses at least partially recover their preexisting levels of diversity,” none of them show potential “for keeping up with the transforming populations of the states or creating greater equity in educational systems, which showed profound inequalities even at the peak of affirmative action” (p.9).

Conclusion

While most of us agree on the noble mission of affirmative action, the fundamental issue is that the presuppositions and personal bias vested in these types of policies cloud our ability to judge with Held’s standards of compassion and care. Inherently, most of us love our families and want the success of our families more than others, which make us skeptical of systems that threaten the power of the groups we identify with (race, gender or class). However, John Rawls’s description of self-interest would oblige society to acknowledge the disadvantages citizens are born with and institute programs to accommodate the less fortunate (Rawls, 1971).

Rawls casts his readers into a theoretical veil of ignorance, preventing them from knowing their parents, or the quality of schools and hospitals in the neighborhood. This veil of ignorance forces readers to acknowledge their own privilege. In this omniscient view we can all acknowledge that statistically speaking, life would be much more difficult in a low-income or underrepresented minority family, especially when going off to college. Furthermore, Rawls urges us to offer accommodations which could tip the scales of justice, to counteract systemic oppression (Rawls, 1971). In this way, it is in our civic duty to diminish inequalities and unfairness by recruiting and retaining low-income and underrepresented minorities at universities for the common good of society.

Many scholars who study affirmative action overlook the concept of self-interest, but I make the case that it is in the self-interest of all of us to strive toward a more robustly diverse society that encourages the success of every individual no matter their socio-economic status, no matter their race, and no matter their gender because we all fundamentally benefit from interactions with diverse groups of people. The benefits of diversity are uncontestable. As the former president University of Michigan states, the educational benefits of racial and ethnic diversity are not theoretical but real and proven repeatedly over time. This is a conclusion embraced both by the Supreme Court in its definitive 2003 ruling on the matter, Grutter v. Bollinger, and by 13 other schools which, along with Columbia, jointly submitted a brief in the Fisher case asserting that diversity encourages students to question their assumptions, to understand that wisdom and contributions to society may be found where not expected, and to gain an appreciation of the complexity of the modern world. Currently, our K-12 education system is segregated (by socio-economic status, race and ethnicity, political leanings, etc.) and this encourages the opposite effects of diversity. Students are in ethnocentric learning environments with those of the same background, and thus have more simple views of the way our world works. Essentially, instead of understanding that any one issue has a multiplicity of answers (which facilitates creativity and innovation), our system encourages simplicity and conformity.

Therefore, diversity appeals to more than those who agree with the ethics of care as a duty to each other, because it is also in our independent, rational self-interest to encourage diverse learning environments. If we believe in freedom of speech we also believe in the value of diverse opinions, which encourages each and every member of society the opportunity to contribute and deliberate. Additionally, if our future leaders are equipped with the innovative thinking skills that can cut across difference, we can collectively accomplish better compromise. Diversity in higher education is essential to the health of our democracy and the underlying values of our constitution and American way of life.

In the wake of recent movements to ban preferential treatment of historically underrepresented groups in Texas and Florida, it is worth investigating whether these solutions are addressing the underlying inequities leading to pervasive achievement gaps between disadvantaged and advantaged students. It remains clear that students from different races do not receive an equal chance for college success, which undermines the normative goal of valuing every student no matter their circumstances as Held suggests.

In Texas, “although white men make up only 48% of the college-educated workforce, they hold over 90 percent of the top jobs in the news media, 96 percent of CEO positions, 86 percent of law firm partnerships, and 85 percent of tenured college faculty positions (Kurland, 2012, p.5). In Florida, “once in college, young white and Asian students are still more than twice as likely as blacks and Latinos to receive B.A. degrees” and the reality is that “almost all the traditional considerations in admissions disproportionately help white students since they are much more likely to be legacies, to have households with more educational resources, to attend more competitive suburban schools, to receive more information about college, and to be able to pay for professional preparation for admissions tests” (Horn and Flores, 2003, p.9). The problem with affirmative action is that while both sides agree that historical exclusion and injustices merit government action, citizens do not agree on how to best achieve these noble ends.

Through the examination of these two similar, yet slightly different approaches to affirmative action my report illuminates whether these plans should be considered successful in achieving greater equity and care for students facing disadvantages from our current systems. While the One Florida plan eliminated the consideration of race altogether, the Texas Top Ten percent law left room for the court decisions to guide university actions. As the data shows, UT has been more successful than A&M in attracting and enrolling minority students and UT reinstated the consideration of race after the court decision in Grutter v. Bollinger. Unlike Texas, the measures in Florida were targeting the K-12 system by making a push for more college readiness at low-income schools. The implementation of this program has been slow moving, as is to be expected with a state-wide shift in education policy, and therefore the ban on affirmative action before the results of the K-12 initiatives have taken effect is ill timed, and could have negatively affected the admittance of minority students. That is, until the university realized that there needed to be a change in policy. Additionally, the recent cuts in the budgets allocated to providing need based merit aid to underprivileged students removes one of the measures that had potential to increase accessibility for low-income and racial minority students.

In addition to the flawed assumption that the K-12 initiatives would immediately yield higher enrollment of low-income and minority students, the One Florida plan shouldn’t be considered successful even after two decades of implementation in improving diversity at the state flagship. As the enrollment rates show, the enrollments of minorities increased after the university had time to incorporate preferential treatment in other admissions procedures such as outreach, and financial aid. However, these enrollment rates also can’t be taken at face value due to the change in 2010 of racial categories, which prompted A&M, and the University of Florida to combine multiple racial categories into “Latino” enrollment, which was the only population that experienced an average increase in enrollment.

Based on the evidence presented in this report, I conclude that both the One Florida plan and the Top Ten Percent law did not create more accessible college options for racial and ethnic minorities. In both cases, the admission of students in the top ten, or twenty percent of their high school class was already standard procedure for most state universities.[6] These laws may have increased socioeconomic diversity but they have done little to account for increased attendance of minorities relative to their share of the population. Additionally, no other factor serves as a proxy for race, which suggests that in order to insure racial diversity the consideration of race would need to be an aspect of the college application. Essentially, if we force our universities to pursue race-blind admissions we ignore prevailing inequalities and have no safeguard for a critical mass of racial minorities.

The positive outcome of both plans was the indirect pressure placed on universities experiencing drops in admission of racial minorities to pursue outreach programs, scholarship programs, and ban legacy preferences that advantage white students. All of these efforts have been proven to increase minority and low-income enrollment. Yet, the caveat here is clear: if universities are using more resources on outreach and financial aid programs to attract minority students, the tuition could go up and make college more unaffordable to everyone. Additionally, the scholarship programs already put in place are being cut, which puts more financial strain on the university. It is essential that policymakers who pass bans on the consideration of race are cognizant of the possibility of increased burden on universities and be sure to fund appropriately.

Based on this comparative case study it seems that state flagship universities can increase racial diversity by banning legacy preferences, instituting outreach programs to disadvantaged schools, and increasing financial aid and scholarships. All of these university measures have the potential to foster racial diversity without having to consider race as a factor in the college application. It will be important to study the implications of the policies on racial diversity in college and university campuses. Future researchers should address the following questions: How can universities incorporate socio-economic and race factors in admissions under the strict scrutiny established by the Supreme Court? How have these laws affected retention and graduation rates of underrepresented groups?

References:

Anderson, Terry. (2004). The Pursuit of Fairness: A History of Affirmative Action, New York: Oxford University Press.

Alon, Sigal and Marta Tienda. (2007). Diversity, Opportunity, and the Shifting Meritocracy in Higher Education. American Sociological Review, 72, pp. 487-511.

Cortes, Kalena. (2010). Do Bans on Affirmative Action Hurt Minority Students? Evidence from the Texas Top 10% Plan. Economics of Education Review, 29, pp. 1110-1124.

Chapa, J. (2005). Affirmative Action and Percent Plans as Alternatives for Increasing Successful Participation of Minorities in Higher Education. The Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 4(3), pp. 181-196.

Charleston, Lavar. (2009). The Dilemma of Higher Education Reform in a Post-Affirmative Action Society: A Review of Anti-Affirmative Action Legislation to Inform Policy Modification. Center for African American Research and Policy, Fall, pp.1-17.

Creusere, Marlena, Carla Fletcher, Kasey Klepfer, and Patricia Norman. (2015). State of Student Aid and Higher Education in Texas. TG Research and Analytical Services.

Crosby, Faye. (2004). Affirmative Action is Dead; Long Live Affirmative Action. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Daugherty, Lindsay, Francisco Martorell, Rand Corporation, and Isaac McFarlin. (2012). Percent Plans, Automatic Admissions, and College Enrollment Outcomes, National Poverty Center Working Paper Series. Retrieved from http://npc.umich.edu/publications/u/2012-18-npc-working-paper.pdf.

Dudley-Jenkins, Laura and Michele Moses. (2014). Affirmative Action Matters: Creating Opportunities for Students around the World. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Florida College Access Network. (2014). College Affordability Adrift: Florida’s Bright Futures Program Faces $347 Million in Cuts by 2017-18. Florida College Access, 8(1), pp. 1-10.

Furstenberg, Eric. (2010). Academic Outcomes and Texas’s Top Ten Percent Law. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 627, pp. 167-183.

Gaertner, Matthew, and Melissa Hart. (2013). Considering Class: College Access and Diversity. Social Science Research Network.

Gillin, Joshua. (2015). Florida has more black, Hispanic university students after ending affirmative action, Jeb Bush says. PolitiFact Florida. Retrieved from http://www.politifact.com/florida/statements/2015/mar/11/jeb-bush/florida-has-more-black-and-hispanic-university-stu.

Gurin, Patricia, Eric Dey, Sylvia Hurtado, and Gerald Gurin. (2002). Diversity and Higher Education: Theory and Impact on Educational Outcomes. Harvard Educational Review, 72(3).

Harris, Angel and Marta Tienda. (2012). Hispanics in Higher Education and the Texas Top Ten Percent Law. Race Soc Probl., 4(1), pp. 57–67. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3584685/pdf/nihms-442056.pdf

Held, Virginia. (2007). The Ethics of Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hicklin-Fryar, Alisa, and Kenneth Meier. (2008). Race, Structure, and State Governments: The Politics of Higher Education Diversity. Journal of Politics, 70(3), pp. 851-860.

Horn, Catherine, and Stella Flores. (2003). Percent Plans in College Admissions: A Comparative Analysis of Three States’ Experiences. The Civil Rights Project Harvard University.

Kahlenberg, Richard. (2012). A Better Affirmative Action: State Universities that Created Alternatives to Racial Preferences. New York: The Century Foundation Press.

Kahlenberg, Richard. (2014). The Future of Affirmative Action: New Paths to Higher Education Diversity after Fisher v. University of Texas. New York: The Century Foundation Press.

Kurland, Richard. Frequently Asked Questions about Affirmative Action. Americans for a Fair Chance. Retrieved from http://www.civilrights.org/equal-opportunity/fact-sheets/fact_sheet_packet.pdf

Lavergne, Gary, and B. Walker.(2002). Implementation and Results of the Texas Automatic Admissions Law (HB 588) at the University of Texas at Austin, Office of Admissions, The University of Texas at Austin.

Long, Mark, Victor Caenz and Marta Tienda. (2010). Policy Transparency and College Enrollment: Did the Texas Top Ten Percent Law Broaden Access to Public Flagships? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 627, January, pp. 82-105.

Lloyd, Kim, Kevin Leicht, and Teresa Sullivan. (2008). Minority College Aspirations, Expectations and Applications under the Texas Top 10% Law. Social Forces, 86(3), pp. 1105-1137.

Marin, Patricia and Edgar Lee. (2003). Appearance and Reality in the Sunshine State: The Talented 20 Program in Florida. Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University, 2003.

National Conference of State Legislatures. (n.d). Affirmative Action: State Action. Retrieved from http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/affirmative-action-state-action.aspx.

News and Views; Let’s Hear the Truth About How Blacks Are Faring Under Jeb Bush’s One Florida Plan. (2004). The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. CH II Foundation, Inc. HighBeam Research. Retrieved from http://www.highbeam.com.

Orfield, Gary and Chungmei Lee. (2005). Why Segregation Matters: Poverty and Educational Inequality. Harvard University Civil Rights Project.

Page, Clarence. (2013). Diversity Means More than Race. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2013-06-26/news/ct-oped-0626-page-20130626_1_abigail-fisher-affirmative-action-case-class-based-affirmative-action.

Post, Robert, and Michael Rogin. (1998). Race and Representation: Affirmative Action. New York: ZONE BOOKS.

Rawls, John. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

The State of Florida Governor’s Office. (1999). Governor Bush’s Equity in Education Plan, November 9. Retrieved from http://edocs.dlis.state.fl.us/fldocs/governor/educationPlan.pdf

Tienda, Marta, and Sunny Xinchun Niu. (2006). Flagships, Feeders, and the Texas Top 10% Law: A Test of the “Brain Drain” Hypothesis. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(4).

Tienda, Marta, Kevin Leicht, Teresa Sullivan, Michael Maltese and Kim Lloyd. (2003). Closing the Gap?: Admissions and Enrollments at the Texas Public Flagships Before and After Affirmative Action. Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

U.S. Department of Education. (n.d) Secretary Duncan’s Remarks on Press Call Highlighting States Where Education Funding Shortchanges Low-Income, Minority Students. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/news/speeches/secretary-duncan%E2%80%99s-remarks-press-call-highlighting-states-where-education-funding-shortchanges-low-income-minority-students.

Walker, B. (2000). The Implementation and Results of HB 588 at the University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved from http://www.utexas.edu/student/research/reports/admissions/HB58820000126.htm.

[†] While at the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce I assisted in the implementation of this program in which counselors offer support over the summer regarding deadlines and important dates/events to begin attending a University for first-generation, low-income students. For more information see Castleman, Benjamin and Page, Lindsay. Summer Nudging, EdPolicy Works, 2013.

[‡] Ward Connerly has been leading the movements in various states to ban affirmative action based on racial preferences through initiating voter referendums. For more information see: http://www.politico.com/arena/bio/ward_connerly.html

[1] “Affirmative action is the process of a business or governmental agency in which it gives special rights of hiring or advancement to ethnic minorities to make up for past discrimination against that minority.” See more at http://definitions.uslegal.com/a/affirmative-action/

[2] However, standardized tests have been proven to disproportionately disadvantage those with less resources, which will be discussed later. See, Alon and Tienda (2007).

[3] Pell Grants are federally funded scholarships to those with household income around 60,000 or lower, therefore this population signifies the low-income representation in student bodies.

[4] See also Robert L. Linn & Kevin G. Welner, Race-Conscious Policies for Assigning Students to Schools: Social Science Research and the Supreme Court Cases, National Academy of Education, 2007.

[5] However, the Florida Bright Futures Program now faces $347 Million in Cuts by 2017-2018. During the 2014 legislative session “the Florida Bright Futures Scholarship Program has been reopened by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights for potentially violating test score requirements, one of the state’s criteria to determine eligibility for the merit scholarship, has the effect of discriminating against students on the bases of national origin and race” (Florida College Access Network 2014).

[6] Until the increase in Texas population, prompting the passage of statutes only requiring state universities to admit up to 75% of the freshman student body of students in the top class ranks.

Thesis Archives

| 2020 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2014 |Copyright ©2025 Ramapo College Of New Jersey. Statements And Policies. Contact Webmaster.