- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

Establishing Protection for Muzzled Victims

TAYLOR PULUSE[1]

Muzzled Victims. In 2010, Baltimore police found a two-year-old Pitbull (Phoenix, as named by her rescuers) doused in gasoline and set on fire in a smoke-filled alleyway. Phoenix was severely burned and had bite wounds all over her body; veterinarians believed some of the bite marks were self-inflicted while Phoenix struggled to “fight off the flames”. Phoenix survived for four days before succumbing to kidney failure and was euthanized. Newspapers, TV and radio stations, and numerous websites publicized Phoenix’s heart-wrenching story, and a twenty-six-thousand-dollar reward was raised to find Phoenix’s attackers. Seventeen-year-old twin brothers Tremayne and Travers Johnson were accused based on identification from a blurred security tape (Bishop, 2011). However, as there was no evidence besides the blurred tape linking the Johnsons to the crime, they were eventually acquitted (Siebert, 2010). Like many other victims of animal cruelty, Phoenix suffered in silence, obtaining no justice for the wanton cruelty she experienced.

In 2015, the Charleston Animal Society and North Charleston Animal Control found a female Pitbull (named Caitlyn by her rescuers) in the streets of Charleston, with her muzzle tightly bound in an electrical tape that cut off blood circulation to her tongue. She was unable to eat or drink. Aldwin Roman, the director of anti-cruelty and outreach in Charleston, who rescued Caitlyn, describes

I remember it like it was yesterday — seeing the fear, the trauma in her eyes, and the excruciating pain she must have been feeling. And I’ll never forget the cry she let out when that tape was finally removed after being on her muzzle for 36 hours — 36 hours of pain, 36 hours of torture (Huspeni, 2017).

The assault on Caitlyn was malicious and deliberate. Caitlyn had been sold to William Dodson for ten dollars, just a week before the assault. Dodson was arrested and admitted to taping Caitlyn’s muzzle. It was later revealed that William Dodson was also wanted on several other weapons and drug charges and had over thirty-one convictions (Huspeni, 2017). He was sentenced to five years (the maximum sentence for animal cruelty) for the torture he inflicted on Caitlyn and an additional fifteen years for the drug and weapons charges. Since her assault, Caitlyn has fully recovered and was adopted by the prosecutor who tried her case.

Figure 1. Photographs of Caitlyn from the Day of Her Rescue and One Year Later (Life with Dogs, 2015)

Companion animals’ subordinate status in society has made them susceptible to abuse and hindered legal protections from abusive circumstances. Phoenix and Caitlyn represent the many victims of animal abuse whom our society has systematically failed. Their stories represent not just instances of animal abuse in society but a systemic pattern of violence committed on vulnerable entities, including women, children, elders, and companion animals, known as the Link. The Link denotes the muzzling of animal and domestic abuse victims by their abusers. Abusive practices towards animals represent a larger societal issue concerning patterns of abuse in domestic contexts. Victims of domestic abuse are silenced by their abusers as a form of control and assertion of dominance. In many ways, animal abuse victims are speechless entities fighting for protection and representation, often from the same domestic abusers. Animals are forced to suffer in silence as there is little recognition of the nature and extent of cruelty. The recognition of the Link between these patterns of muzzling in intimate spaces is important, as it challenges the toxic culture of subordination in our society.

In this essay, I will analyze the underlying factors of animal cruelty and abuse of companion animals in the US from the vantage of the Link. I will examine how factors such as masculine power structures, psychological disorders, exposure to domestic abuse, subjection to corporal punishment, and the lack of recognition for animal rights lead to animal cruelty. My paper claims a right to legal guardianship for companion animals and offers recommendations on how animal abuse against the family pet can be prevented by addressing the Link. Although numerous philosophers and scholars have studied the connection between animal abuse and domestic violence for centuries, the concept of Link is under-recognized by law enforcement, healthcare professionals, and society. As a result, little has been done to protect companion animals from abuse within their homes. The Link references the concurrence of multiple crimes against humans and animals alike. In addition, the Link shows how individuals who abuse family pets are more likely to participate in other forms of criminal activity. By confronting the Link society can not only identify the abuse of a family pet and the abuse of children, elders, spouses and/or relationship partners but also prevent future violence from arising within communities.

Confronting the Link. Ethical Perspectives

He who is cruel to animals becomes hard also in his dealings with men. We can judge the heart of a man by his treatment of animals.

– Immanuel Kant

The notion that cruelty towards animals impacts humans is an expansive idea in philosophical discourse. Philosophers have observed animal abuse’s detrimental consequences as early as the seventeenth century (Arluke, 2006). In 1693, John Locke propounded “that harming animals has a destructive effect on those who inflict it” (Arluke, 2006, p.2). John Locke famously wrote in reference to children, in Some Thoughts Concerning Education, “For the custom of tormenting and killing of beasts, will, by degrees, harden their minds even towards men; and they who delight in the suffering and destruction of inferior creatures, will not be apt to be very compassionate or benign to those of their own kind”(1808, p.228). Locke ultimately highlighted that animal cruelty represents a degradation of respect for life. Following John Locke’s footsteps, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant advanced the ethical foundations for the animal rights movement. Kant believed that cruelty towards animals is significantly problematic because it cultivates insensitivity. Kant argued that we should not be cruel towards animals because causing them pain significantly affects us. Exposure to cruelty desensitizes individuals to the actions of causing pain and creates a higher probability for individuals to inflict pain upon other individuals.

Locke and Kant were the first to address the underpinnings of the Link as they recognized the interrelatedness between aggression toward animals and individuals (Branham, 2005). During the 19th century, the famous British utilitarian philosopher, John Stuart Mill, added additional reasons why cruelty towards animals and causing pain is “ethically objectionable” (Branham, 2005). Mill held that “actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness: wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain and the privation of pleasure” (1957, p.10; also cited in Branham, 2005). Mill’s Greatest Happiness Principle recognized animals, as sentient beings, that have the capacity to feel both pain and pleasure. Mill argued that “the end of human action, is necessarily also the standard of morality; which may accordingly be defined, the rules and precepts for human conduct, by the observance of which an existence such as has been described might be, to the greatest extent possible, secured to all mankind; and not to them only, but, so far as the nature of things admits, to the whole sentient creation” (Mill, 1863).

In the late 20th century, the moral philosopher Peter Singer and the anthropologist Margaret Mead brought ethical perspectives on animal rights to a modern context. Peter Singer extended John Stuart Mill’s utilitarian theories and argued that animals suffer in vast numbers to serve humans “mundane” pleasures. Singer believed that we as humans sacrifice the most important interests of one species to satisfy our most trivial interests (Branham, 2005). Singer addressed the overall lack of morality regarding the treatment of animals in our society, while Margaret Mead took a more direct approach to the cause of animal cruelty and the cycle of violence it instills. Mead emphasized that animal cruelty could be a direct symptom of some form of a “character disorder” (Arluke, 2006). Mead’s argument focused on animal abuse at the hands of children and adolescents. Mead argued that children and adolescents who abused animals were “on a path to future violence” as they were desensitized and triggered “an underlying predisposition to aggression” (Arluke, 2006). In this manner, animal cruelty was seen as a gateway crime that opened the door for adolescent abusers to inflict violence against future targets such as humans. Although it is apparent that there have been significant debates recognizing aspects of the Link and the detriments it possesses for society, such debates were never put in practice until recently.

Likewise, social scientists have documented the link between abusive behavior toward animals and violence directed toward humans. They have noted that animal cruelty is similar to domestic violence, as it is not contained in a specific social sphere; rather, “it crosses all educational, ethnic, and socioeconomic barriers” (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.8). The abusive practices have been classified into seven non-mutually exclusive categories: passive, participatory, perfunctory, parochial, partitive, psychological, and predatory. The typology of animal abuse provides a clearer understanding of the “various manifestations of animal cruelty”, aiding recognition of the levels of abuse. Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, in the Silent Victims Recognizing and Stopping Abuse of the Family Pet, observe

Animal abuse cases resulting in convictions have reported such cruelties as beating, stabbing, burning, drowning, hanging, fighting, hoarding, poisoning, shooting, throwing against a wall or out a window, neglect (including intentional starvation of an animal and neglecting to provide adequate food, water, shelter, stimulation, emotional attention, and veterinary care), torture, choking, mutilation, bestiality, and kicking (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.4).

Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan argue that a broadened perspective of the crime of animal abuse allows for a more explicit recognition of the warning signals that aid intervention and prevention (2006, p.3). The vulnerability of animals in our society makes them more susceptible to multifaceted abuse inflicted by abusers.

Convictions and legal actions brought against animal abusers rest upon how the abuse is defined and the crime of animal cruelty constructed. Studies show that non-violent and violent attitudes about pets develop and are influenced within a family context (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.26). If a child is exposed to animal abuse, the child will likely develop similar sentiments of aggression and violence towards animals. If a child is taught to be kind to animals and treat them as entities that deserve respect, they are likely to grow into adulthood with the same ethical perspectives from their childhood. The crime of animal cruelty needs to be recognized and the violent cycle needs to be broken.

Since companion animals are fully dependent on their families to provide necessities such as food, water, and shelter, they are especially vulnerable to different forms of abuse (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.27). Animal abuse can be easily concealed as animals cannot obtain help outside their homes and alert others to the abuse they are experiencing. Additionally, one reason why numerous cases of such abuse go unpunished is because animals do not have a means of communicating and identifying their abusers to authorities (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.27).

Understanding the Link

Since animals cannot advocate for themselves, society must recognize the evident patterns of violence and control that correspond with their abuse. Many animal advocates refer to the connection between animal abuse and domestic abuse as the Link. The National District Attorneys Association defines the Link as

…the coexistence of two or more of the intra-familial crimes: child abuse (including physical and sexual abuse) or neglect, domestic violence (including stalking and rape), elder abuse or neglect (including financial exploitation), and animal abuse or neglect (including sexual assault, animal fighting and hoarding) (Phillips, 2014, p.5).

In addition to the disturbing acts listed above, the Link also includes the concurrence of animal abuse with other types of crimes such as homicide, weapons offenses, drug offenses, sexual assault, arson, assault, or other violent crimes (Phillips, 2014, p.5). In relation to the Link, there are numerous shocking statistics derived from the testimonies of abuse victims to support that such connections exist. According to the American Humane Association, over a million children fall victim to abuse within their homes. In addition, an unknown number of family pets also take on the role of the victims in the same violent households (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.28). According to Silent Victims Recognizing and Stopping Abuse of the Family, one study examining the Link between animal abuse and domestic abuse reports,

80% of domestic violence victims reported batterers had abused pets by kicking, beating, punching, mutilating, extreme neglect and killing of pets. Animal abuse was done in front of female victims in 87.7% of the cases and in the presence of their children in 75.5% of the cases (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.31).

It is also clear that in many domestic violence cases the victim’s pet is often targeted as a means of breaking bonds and establishing entire control over victims. Batterers often isolate their victims from any solace they may seek. Since it is a known fact that companion animals offer emotional support to their owners, they are often the first ones to fall victim to the hands of abusers (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.27). Batterers will in fact prey on the vulnerability of their victims, especially companion animals, to enforce their dominance within a home. Companion animals become the perfect victims for abusers as they have no voice to report the abuse they are enduring.

The stories of abused animals published in the media by advocates become the only voice publicizing the Link for society. By observing the most extreme cases of animal cruelty, the prominence of the Link can be easily identified. Animal rescuers are considered the frontline combatants that fight to protect companion animals from the abusers of society. Megan Brinster, the executive director of the Ramapo Bergen Animal Refuge, has recognized that the Link plays a significant role in many of the abuse cases the shelter sees (Brinster, 2020). The Refuge has bared witness to some of the most heinous acts of animal cruelty, such as intentional burning with a blow torch and deliberate starvation. When asked how she recognizes the Link’s presence in society, Brinster stated that abused companion animals are the “unspoken victims of the greater issues in society.” Animals are left as voiceless victims that desperately rely on shelters and animal advocates to protect them from their abusers. In many respects, animals rely on humans to tell their stories and fight for their right to protection. It is our responsibility to form advocacy networks and educate society on the violence that the Link perpetuates.

Why Should We Care?

The issue of animal abuse against the family pet needs to be addressed more critically within the United States. The current laws against animal abuse are both insufficient and inconsistent in establishing justice for the innocent animals that fall victim to the heinous crime. Addressing animal abuse within the family home can save lives, as incidents of abuse are unisolated and have human victims as well. Dr. Pamela Carlisle-Frank and Tom Flanagan, leading animal rights scholars, explain that the reason why society as a whole needs to address animal abuse more critically centralizes around the fact that experiencing and witnessing abuse leads to future patterns of violence in society (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.17). Besides the evident factor that innocent animals suffer, studies have shown that children who witness the abuse of their family pets at the hands of their parents are more likely to not only abuse animals themselves, but also become violent towards individuals (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.17). It is essential to recognize that the abuse of an animal due to conduct or mental disorder is increasingly more dangerous and sometimes deadly for an entire community. When animal abusers recognize that they could inflict harm upon an animal and go unpunished for their crimes, the abuser’s deviant behavior can escalate. Within Silent Victims: Recognizing and Stopping Abuse of the Family Pet by Dr. Pamela Carlisle- Frank and Tom Flanagan state, “Left unchecked, conduct disorder is likely to result in more violence, possibly in the form of fires intentionally set to private homes” (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, 18). It is evidently clear that animal abuse, more specifically the abuse of a family pet, is a disturbing phenomenon whose “spillover effects” increase violence and threaten both individuals and society (Carlisle-Frank & Flanagan, 2006, p.19). To allow the abuse of the family pet to go unhindered in society is to allow for a toxic environment to thrive and threaten the lives of humans and animals alike.

Scholars reporting on the causalities contributing to animal abuse and the Link have identified numerous factors influencing the disturbing phenomenon. Animal rights advocate Carol J. Adams has argued that the “patriarchal culture” interwoven into society contributes in one way or another to the victimization of companion animals. Adams believes that the masculine power structures that arise from patriarchal culture disturb the peace within homes and lead to domestic abuse (Adams, 1994, pp.63-84). Adams recognizes that patriarchal culture propels toxic forms of masculinity as male sexual identity is constituted by dominance and power. Other scholars such as Arnold Arluke and Clifton P. Flynn argue that animal abuse occurs in cycles in which children are influenced by their parents’ actions and children oftentimes continue the chain of abuse. More specifically, Clifton P. Flynn blames corporal punishment on children as a direct trigger associated with the participation of animal abuse (Flynn, 1999, pp.971-981). There are also psychiatric disorders that are also displayed in connection with the mental state of animal abusers. Scholars such as Roman Gleyzer, Alan R Felthous, and Charles E. Holzer argue that antisocial personality disorder (ADP), a disorder characterized by the inability to empathize, is a common constituent in the mentality of animal abusers (Gleyzer, Felthous, and Holzer, 2002). It is abundantly clear that we as individuals must address the Link more diligently to promote a safer world for animals and humans. Each of the factors listed above will be more critically explained and evaluated in the next section.

Examining the Factors Contributing to the Link

Abuse enacts a value hierarchy- through abusive behavior a person establishes control, becoming “up” rather than “down”- while originating in value hierarchies: those who are “down” in terms of (public) status- women, children, non-dominant men, and animals are more likely to be victimized.

– Carol J. Adams

Throughout history, women and animals held the same legal position as the property of men. Women’s status in society somewhat progressed as they used their voices to protest the oppression they faced. Unfortunately for animals, they were forced to suffer in silence as the forgotten victims of patriarchal culture. The gendered hierarchy of our society has infiltrated familial constructs and perpetuated both domestic abuse and animal abuse in our society. The submission and domination over victims, supported by the patriarchal culture, is the underlying contributing factor to the Link. Whether or not partners, parents, or individuals (of any age) inflict harm in a relationship, the purpose of the abuse is to secure and maintain a heightened level of authority over victims.

Masculine Power Structures

Some factors that directly contribute to and continuously stimulate violence within our society are its masculine power structures. Gender constructs in our society embody unequal power distribution, especially within households. The interconnected forms of violence displayed in the Link contribute to and continue inequality between genders. In patriarchal culture, animals become feminized as entities of subordinate status, just like women (Adams and Donovan, 1995, p.80). Toxic masculinity arises as a condition of patriarchal culture constructing male identity around the idea of authoritative control (Adams and Donovan, 1995, p.80). When society teaches men to act and behave as superior beings, toxic masculinity directly produces the abuses relating to the Link. Teaching males within our society about a gendered hierarchy has led to the abuse of numerous “feminized bodies.” Violent men taking their aggression out on their family members and animals has been normalized in our culture throughout history. Patriarchal culture plays a significant role in familial dynamics and forces significant vulnerability upon women, children, and animals within a societal setting.

In the early 1980’s, the feminist philosopher Elizabeth Spelman formulated the term somatophobia. Spelman recognized sentiments of masculine control in society and found deep connections between such control and the abuse of disenfranchised bodies (Adams and Donovan, 1995, p.80). As explained within Animals and Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations, “Spelman coined the term somatophobia to denote the equating of women, children, animals, and “the natural world” with one another and with the despised body” (Adams and Donovan, 1995, p.80). Somatophobia is described as being symptomatic of a combination of multiple social inequalities such as sexism, racism, classism, and speciesism (Adams, 1994, p.2). Somatophobia is enacted in “unequal relationships” in which masculine control is exerted or displayed (Adams, 1994, 2). Abusive relationships between men and women, fathers and children, and humans and animals demonstrate the condition of somatophobia and offer understanding of the oppressive nature of patriarchal culture (Adams, 1994, p.2). Somatophobia represents the shared historical oppressions between women, animals, and other disenfranchised bodies. Spelman acknowledges that the concept of masculine control is a direct product of patriarchal culture which assumes that men possess a distinct superiority separating them from women and animals (Adams, 1994, p.2). One very prevalent configuration of somatophobia correlates to a trifecta in which an abusive man harms women, children, and animals. A dominant theme found within the testimonies of survivors of domestic abuse presents the relationship between control and sexual victimization. In many cases of domestic abuse, companion animals are targeted (by either threats or actual killings) and used to establish and/or maintain control over sexually victimized women and children (Adams, 1994, p.2).

Masculine Control and the Notion of Property

In numerous domestic battery cases, masculine power structures within the home are revealed. Frequently a woman or child’s domestic abuser threatens and inflicts serious harm upon the victim’s pet or pets to display his/her domination and control. In many circumstances, pets are held hostage by batterers to ensure the submission of their victims (Adams, 1994, p. 2). The Ramapo Bergen Animal Refuge has witnessed the extent abusers will go to remain in control over their victims. Battered women will surrender their companion animals to the Refuge to protect them from their abusers. Whether the batterer is abusing the women and animal directly or using the animal as a tool to assert control, abuse victims will attempt to save/protect their pets by surrendering them to shelters or refuges. In many cases, the alleged abuser will call the shelter and attempt to get the companion animal back under their control (Brinster, 2020). It is evident in such cases that the victims are attempting to protect their companion animals from abuse and eliminate an element of control their abuser preys upon.

When a batterer/abuser kills a victim’s companion animal, the action is identified as a “destruction of property.” In all cases of battering, the abuse inflicted upon victims should not be recognized as a loss of control for the batterer, but rather the achievement or reinforcement of control. Battering is a form of teaching and reiterating subordination to abuse victims. In all domestic abuse cases, the notion of property is directly related to masculine controls (Adams & Donovan, 1995, p. 59). When observing patterns of battery, the relationship between sexual violence and the destruction of property/pets is often overlooked. Battery and domestic abuse are centralized around a hierarchy within a household. Male batterers recognize the women, children, and companion animals within their home as their property. The violence inflicted upon the batterer’s “property” is used to reinforce the subordination of victims and maintain supremacy/mastery within a home. As Carol Adams states in Animals and Women

Recognizing harm to animals as interconnected to controlling behavior by violent men is one aspect of recognizing the interrelatedness of all violence in a gender hierarchical world (Adams & Donovan, 1995, p. 80).

Harming animals becomes an instrument of strategic expression for batterers in which patterns are evidently recognized through masculine controls over women.

In such acts of destruction, the batterer’s essential goal is to “affect” their human victims. When an abuser attacks both a human victim and their companion animal, he/she achieves a level of “double control” in which domination is achieved over two living entities (Adams and Donovan 1995, p. 59). Anne Ganley, a pioneer psychologist in victim-based counseling for batterers, observes that

The offender’s purpose in destroying the property/pets is the same as in his physically attacking his partner. He is simply attacking another object to accomplish his battering of her (Adams 1994, 66).

Whether or not the victim in this circumstance is physically attacked, watching the battering of their companion animal possesses the same psychological impacts as a physical attack would.

The emotional support that companion animals provide is considerably heightened for victims of domestic abuse. Companion animals become critical sources of “comfort and affection” in abusive situations (Adams, 1994, p. 67). For victims, the death of their companion animal at the hands of their abusers symbolically represents their own death, and the killing of their pets represents an obliteration of their hope (Adams, 1994, p. 66). When companion animals are executed at the hands of batterers, victims are violently separated from the support network their companion animal once offered. Companion animals become objectified as instruments of intimidation, violation, and coercion for batterers to maintain masculine control over their victims. Like many cases concerning domestic battery, child sexual abuse cases also expose the harsh realities of masculine controls. By studying the testimonies of survivors of child sexual abuse, one can recognize there is a pattern between establishing control through the abuse of a companion animal and the insurance of a victim’s silence. One commonality that arises in the testimony of such victims is that abusers would often make their victims decide between their pet’s death or their physical abuse (Adams, 1994, pp.66-67). The bond between a victim and their companion animal is heavily preyed upon in this manner.

Corporal Punishment, Masculinity, and Abuse

Forwarding animal abuse’s connection to masculine controls, an empirical study performed by Clifton P. Flynn at the University of South Carolina displayed disturbing results regarding the subject. The study examined 267 male and female college undergraduate students. The sample was considered predominantly Caucasian, with African American respondents composing only one-fifth of the sample (Flynn, 1999, pp.971-981). The students in introductory Sociology and Psychology classes were required to complete an eighteen-page questionnaire that asked questions regarding demographic information, familial background, any experiences with family violence, and any experiences with animal cruelty. The study revealed shocking statistics regarding the frequency of corporal punishment and its connections to animal abuse. One of the first shocking revelations was that forty-nine percent of the study’s participants had been exposed to animal abuse, whether they physically participated in the crime or witnessed the crime occurring. Of the forty-nine percent of individuals exposed to animal abuse, eighteen percent (forty-seven of the respondents) admitted to perpetrating the act on more than one occasion. Furthermore, the students admitted to using methods of abuse such as hitting, beating, kicking, or throwing an animal against a wall. Approximately forty percent of the forty-seven respondents who admitted to abusing an animal stated that they were between the ages of six and twelve when they first participated in the crime. Additionally, a shocking eleven percent admitted to committing their first act of animal cruelty when they were between the ages of two and five. The study recognized that nearly two thirds of the individuals who perpetrated the act of animal cruelty had done so in their adolescents (Flynn, 1999, pp.974-975). This finding relates directly to the cycle of violence that perpetuates through the Link. As children and adolescents become exposed to violence and abuse within their homes, their aggressive behaviors are often carried into adulthood and later instilled into their children.

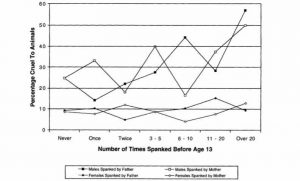

The study also revealed that the individuals punished more frequently by their parents, especially their fathers, were more inclined to commit animal cruelty. The study concluded that there is an evident relationship between the frequency of corporal punishment received by an individual and the execution of animal abuse, primarily for males who were spanked by their fathers throughout their adolescence. Disturbingly, roughly sixty percent of males who were subjected to frequent (ranging from twenty or more incidents) corporal punishment at the hands of their fathers had committed animal abuse ((Flynn, 1999, pp.975-976). It is important to note the study did draw into focus the subjection of individuals to corporal punishment at the hands of their mothers and concluded that “no real pattern had emerged.” Additionally, for females who were subjected to corporal punishment, there were considerably low rates of animal cruelty and “unrelated” frequencies regarding punishments from either parent (Flynn, 1999, p.977). Figure 3 below presents the percentages of respondents who admitted to committing animal cruelty, divided by gender, with a corresponding “spanking frequency” category delivered by both their mothers and fathers (Flynn, 1999, p.977).

Figure 2. Frequency of Preteen Spanking and Perpetration of Animal Cruelty, By Gender of Respondent and Parent (Flynn, 1999; p.976)

Ultimately, the University of South Carolina University study led to shocking revelations regarding factors contributing to the Link. The report unveiled that the rate in which males are likely to commit animal abuse is roughly four times greater than that of females. The masculine tendencies that are vastly apparent within the family home further reinforce domestic violence and abuse. It is clear that the relationship between the gender of an abuser and the gender of a victim does play a role in the perpetration of animal abuse. It is also apparent that there are direct connections between “male socialization”, corporal punishment, and animal abuse. This connection draws into perspective the societal constructs in which males are expected to be “hyper” masculine. In numerous homes throughout the nation, males are subjected to physical punishments more frequently than females. In addition, the physical punishment of males is generally much harsher (Flynn, 1999, pp.977-979). This rationale relates directly to “cultural spillover theory”, in which the theory argues that at an individual level, the greater exposure to culturally acceptable violence, the more likely one is to engage in culturally unacceptable violence (Flynn, 1999, p.972). In relation to the study, the more sons were subjected to “culturally legitimate punishment” at the hands of their fathers, the more likely they were to engage in the “socially unacceptable violence” of animal cruelty (Flynn, 1999, 979). Consequently, young males subjected to corporal punishment learn to appropriate the physical violence they are subjected to and begin to “rehearse” the interpersonal violence stemming from their abuse directly on innocent animals (Flynn, 1999, p.980).

Micro-Environments and Exposure to Domestic Violence

When assessing the factors that contribute to animal abuse one of the greatest impacts on the behavior of animal abusers is their micro-environments. Micro-environments, also known as “proximal environments”, refer to a child’s family and parenting experiences and are crucial conditions in determining the causation of animal abuse. Exposure to frequent levels of violence has the ability to desensitize an individual. Studies have long proven that witnessing aggression leads to development in aggressive behaviors. In a 2005 study, Anna Costanza Baldry, a social psychologist and criminologist, discovered that adolescents or “youth” who witness domestic violence or animal abuse are three times more likely to be cruel towards animals when compared to their peers without such experiences (Gullone, 2014, pp.61-79). Aggressive and violent behaviors become psychologically transformed as “normative behaviors”. This connection is significantly discussed in “human aggression literature” where there is a theory that a child’s beliefs about aggression and violence specifically correlate with those of their parents (Gullone, 2014, pp.65-67). Gullone in his article Risk Factors for the Development of Animal Cruelty argues

Children who witness or directly experience violence or aggression have been documented to be more likely to develop ways of thinking and behaving that support aggression and a tendency to behave aggressively ( 2014, p.67).

Essentially, the greater the instability and violent conflict within a family home, the greater the likelihood of children developing “childhood-onset antisocial behavior” (Gullone, 2014, pp.68-70).

Psychiatric Disorders

Dating back to the early seventeenth century, physicians have researched the relationship between aggression towards animals and humans with various psychological disorders. Following in the footsteps of John Locke, the celebrated French physician Phillipe Pinel (also known as the founder of “moral treatment”) developed the psychiatric concept “mania without delirium”. “Mania without delirium” meant that an individual has a mental disorder that did not change the cognitive functions of their brain. Individuals who suffered from “mania without delirium” experienced high levels of impulsivity and would consistently act out aggressively. One of the examples Pinel used to explain the disorder involved a man who possessed extremely high levels of aggression toward people and animals alike and eventually murdered a person. Today, “mania without delirium” is known in the scientific and psychiatric communities as Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD) (Gleyzer, Felthous, & Holzer, 2002, p.257).

In Texas, a 2002 study conducted by Roman Gleyzer, Alan R. Felthous, and Charles E. Holzer III, the history of animal cruelty in childhood was tested to unveil the association with the diagnosis of APD in adulthood. The study utilized “retrospective forensic chart review” on a total of ninety-six individuals. Forty-eight individuals in the study were criminal defendants with a recorded history of substantial cruelty towards animals. The control group for the study included randomly selected criminal defendants matched for sex, age, race, and year of examination and had “no history whatsoever of animal cruelty”. The subjects were asked interview questions that followed a specific outline addressing early childhood behaviors, demographics, and family background. Additionally, all of the individuals were subject to a “comprehensive Mental Status Examination” (Gleyzer, Felthous, & Holzer, 2002, pp.257-258). The researchers used the chi-square test of independence with correction for continuity to make most of the comparisons between the groups. The study discovered that the group of subjects that possessed a history of animal cruelty displayed significantly higher levels of polysubstance abuse and dependence. Moreover, the study also confirmed its initial hypothesis that the diagnosis of APD was notably more frequent in the group with a history of animal cruelty ((Gleyzer, Felthous, & Holzer, 2002, pp. 258-260).

Table 1 below illustrates that 37.5% of the individuals who possessed the history of animal cruelty (the “Study Group”) had APD. Furthermore, Table 1 also displays that individuals in the study group also possessed significantly higher percentages relating to other personality disorders that have “antisocial features”. Almost 80% of the study group possessed a “character pathology with antisocial traits”. This revelation is shocking when compared to the control group who only possessed 20% of such traits. In relation to the category titled “all personality disorders”, 75% of the study group fit into this category although only 27.1 percent of the control group had. The study ultimately propounded that there is a significant connection between the history of animal cruelty and personality disorders in general, regardless of the specific nature of the disorder (Gleyzer, Felthous, & Holzer, 2002, pp.261-262). The crime of animal cruelty is categorized as one of several antisocial behaviors that are typically considered conduct disorders in childhood. The results of this study suggest that the possession of a history of animal cruelty needs to be looked at more critically in terms of the evolution of conduct disorders in childhood transforming into more serious pathological behaviors in adulthood (Gleyzer, Felthous, & Holzer, 2002, p.262).

Table 1. Personality Disorders and Possessing a History of Animal Cruelty (Gleyzer, Felthous, and Holzer, 2002; p.261).

By recognizing how each of these factors contributes in one way or another to the Link, we as individuals can examine how various elements cause present and future violence in our society. The factors referenced above possess dominant connections with each other. Such connections allow us to observe the Link in a larger societal setting. By addressing each of the factors that stimulate the abuse of “disenfranchised” bodies in our society, we as individuals can create safe holds to address and stop the tangled cycle of abuse from occurring. The following section will address how law enforcement, healthcare professionals, and society can prevent abuse and violence for the salvation of both human and animal victims.

Addressing the Gaps in Protections

“We must fight against the spirit of unconscious cruelty with which we treat the animals. Animals suffer as much as we do. True humanity does not allow us to impose such sufferings on them. It is our duty to make the whole world recognize it. Until we extend our circle of compassion to all living things, humanity will not find peace.”

-Arthur Schopenhauer

The crime of animal cruelty possesses a dangerously high potential to reinforce and create future violence within our society. There are extreme gaps within the networks of protection for domestic and animal abuse victims. Professional groups’ lack of recognition of the Link has led to a growing number of domestic and animal abuse cases unhindered in our society. Establishing a network of protectors throughout various professional fields can, in fact, aid in preventing domestic and animal abuse in society. Fields such as veterinary, social work, and law enforcement should all be provided with proper training to help close the gap in the flawed protections of companion animals. Proper training on the Link can allow such professionals to recognize the connections and warning signs of domestic and animal abuse. Recognizing the areas where the gaps of weak protections are prominent allows for a good network of protectors to be provided for the muzzled victims in our society.

Better Education for Veterinarians

Compared to other countries such as Canada, the United States has been considerably slow to build strong interrelations between veterinary involvement and the Link. In December of 1999, Canada passed Bill C-17, which raised the maximum penalty for intentional animal cruelty to five years in prison and permitted judges to prohibit the ownership of animals for anyone convicted of cruelty. Additionally, the legislation recognized veterinary involvement and gave judges the authority to order restitution to veterinarians who care for abused animals. In a survey conducted by R.E. Landau, the deans of 31 American and Canadian schools of veterinary medicine, researchers were determined to assess the role of veterinarians in recognizing and reporting animal abuse to authorities. The survey’s objective was to evaluate the connections between veterinary involvement and the treatment of animal injuries associated with ongoing or potential violence/abuse. Within the survey, 97% of the deans agreed that veterinarians would encounter situations in their careers where intentional animal abuse was apparent.

Moreover, 63% of the deans agreed that veterinary professionals would encounter instances of apparent animal abuse associated with family violence. However, only 16% of deans reported that veterinary students were explicitly aware of policies on the correct response to suspected abuse (Lockwood, 2000, p. 867). Although the deans widely recognized the connections of the Link, based on inquiries gathered by The Humane Society of the United States, numerous veterinary students felt that the issue of animal abuse was “inadequately addressed in their training.” Even more shocking, researchers estimated that an average of only eight minutes is spent in the veterinary curriculum on the issue of the Link. In this manner, it is apparent that numerous veterinary professionals are uncertain about the role they can/should play in such abuse cases (Lockwood, 2000, p. 877).

In order to understand and adequately address the level of uncertainty among veterinary professionals, recognizing the root causes of such uncertainty is crucial for the prospect of improvements. Randall Lockwood, the Vice President of the Research and Educational Outreach of The Humane Society of the United States, recognizes that there are four main reasons why veterinarians experience uncertainty when addressing animal abuse. The first and most widely apparent reason is that there is no standard for identifying injuries in veterinary patients that directly result from intentional abuse or extreme cruelty/neglect. As a result of such ambiguity, veterinary involvement in cases of animal abuse is limited to cases with “unequivocal evidence of intentional harm.” Second, within the veterinary curriculum, veterinarians are trained to base the diagnostic assessments of their patients on the facts presented to them by their owners. Thus, numerous veterinarians possess an underlying level of trust in their patient’s owners leading them to believe that the facts being provided to them are true. Third, when veterinarians recognize suspected cases of intentional abuse (and possible abuse of human family members), they may experience a legitimate concern about their safety and their staff. Such reasoning causes serious underreporting of animal cruelty cases. Lastly, there is serious inconsistency regarding legal mandates and protections regarding veterinary responses to suspected abuse in the United States (Lockwood, 2000, p. 877). The American Veterinary Medical Association places the responsibility of reporting cases of abuse on the appropriate authorities at the hands of veterinarians. As stated by Lockwood,

currently, reporting suspected cruelty to animals is required in only a few states, including West Virginia, Minnesota, and Alabama. Other states (Arizona, Wisconsin, and California) only mandate veterinarians to report suspected abuse related to dog fighting. Some states (Idaho, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, New Jersey, California, Florida, and Arizona) encourage abuse reporting by providing immunity for veterinary professionals who make good-faith reports (2000).

There are significant discrepancies in reporting suspected animal abuse cases state-by-state. In addition, the mandates for veterinarians to report such cases are also inconsistent as some do not specifically define veterinarians as mandated professionals to report such abuse (Lockwood, 2000, p. 877). To resolve the levels of uncertainty, the United States must clearly define veterinarians as mandated professionals, set legitimate standards for veterinarians to recognize injuries/conditions of intentional abuse, and add substantial training and lessons to the veterinary curriculum. By adjusting the level of involvement of veterinarians in abuse cases concerning the Link, veterinarians have the potential to be one of the many strongholds against the progression of violence in society. In addition, educating veterinarians on how to recognize animal cruelty and the proper avenues to take in response to its identification is crucial in establishing a better protection system against animal abuse.

Asking the Right Questions

Other fields where strongholds can be created to prevent animal abuse within society are within human service careers. Individuals who directly work with victims of domestic abuse, such as clinicians, counselors, and social workers, should be required to ask more pressing questions about the presence of animal abuse within the victim’s home (Flynn, 2000, pp.87-95). By asking pertinent and insightful questions, the cycle of abuse perpetuated through animal cruelty exposure can be halted. Furthermore, assessment techniques need to be further developed for human service professionals to recognize the numerous patterns of abuse that correspond with the Link. There have been two assessment techniques created in relation to the Link for human service professionals to utilize when questioning victims of domestic abuse. Leading psychology professors at Utah State University, Frank R. Ascione, Teresa M. Thompson, and Tracy Black, developed the Children and Animals (Cruelty to Animals) Assessment Inventory (the CAAI) in 1997. The CAAI is a “semi-structured” interview specifically designed for questioning children over the age of four and their parents. The CAAI focuses explicitly on the abuse of an animal being perpetrated by minors (Flynn 2000, 94). As stated within the article “Why Family Professionals Can No Longer Ignore Violence toward Animals” by Clifton Flynn regarding the CAAI,

This inventory taps multiple dimensions of animal cruelty, including severity, frequency, duration, recency, diversity (across within and within categories), animal sentience level, covert (degree to which child tries to hide the cruelty), isolate (individual vs. group cruelty), and empathy (expressions of remorse or concern for animal victim) (Flynn, 2000, p.94).

The line of questioning utilized by the CAAI allows professionals to understand the extent of the violence occurring within the family home. More importantly, the CAAI allows professionals to assess the abuse being inflicted by the minor. Similar to the CAAI, the Boat Inventory on Animal-Related Experiences (the BIARE) was developed in 1999 by Barbra W. Boat, a licensed clinical psychologist. The BIARE was created to aide professionals in screening and gathering information to determine “if an individual’s history includes animal-related events involving trauma, cruelty, or support.” The BIARE includes questions concerning numerous areas of “pet ownership history.” Questions regarding animal-related fears, animal loss, killing, and animals used to coerce/control a person are all assessed within the Inventory. Through such assessments, professionals can seek solutions that protect the family pet from future abuse and help the abuser receive the professional help they require to stop their aggressive behavior(Flynn, 2000, p.94).

Properly Training First Responders

First responders are often the first line of defense for victims of domestic and animal abuse. It is evident however, that there are serious issues surrounding the reporting, investigation and prosecution of the crime of animal cruelty. In order to alleviate some of the central issues corresponding with the criminal apprehensions of abusers, additional training needs to be provided to animal control officers, first responders, investigators, and prosecutors. As stated in Animal Cruelty as a Gateway Crime by the National Sheriff’s Association,

Although several animal care and control groups have trainers throughout the country and provide free training for law enforcement, often the time commitment necessary and cost involved in taking an officer from his or her designated assignment prohibits many agencies from taking advantage of these courses (National Sheriff’s Association, 2018, p.3).

The priorities of most law enforcement agencies are often set on crimes that are considered high profile. Especially in the case of local law enforcement agencies, animal abuse crimes are not considered at the same level as “human crimes”, so investigations concerning animal crime offenses are often not as “followed-up on” as other crimes. An additional issue pertaining to large-scale training of law enforcement, is that the United States possesses a variety of jurisdictional requirements, and organizational policies/ procedures. Therefore, there is some level of difficulty to establish a universal curriculum that encompasses all states. Due to the presence of the Link however, comprehensive and systematic training of first responders has become increasingly important. Although some police academy directors have started to include “short modules of instruction on animal crimes”, most police academies are focused more on state and agency mandated courses. Moreover, as a result of limited budget, many academies cannot afford to include the crime of animal cruelty in their standard recruitment curriculum (National Sheriff’s Association, 2018, p.3).

For many years the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) grouped and defined animal abuse under the label of “Other”. Animal abuse was categorized with numerous “lesser crimes” which essentially made it hard to discover and track. In 2014, the FBI announced to the public that the crime of animal cruelty would be categorized with other “Class A” crimes such as homicide and assault. In 2016, continuing its recognition of animal cruelty as a more serious crime, the FBI began collecting data and mandating law enforcement agencies to report incidents of animal cruelty. The FBI focuses on data derived from arrests and reported incidents in four main areas. The first area concerns arrests and reports made for the “simple or gross neglect” of an animal. The second area regards any arrests and reports filed on an abuser that intentionally abuses and torture an animal (National Sheriff’s Association, 2018, p.3). The third area focuses directly on the “organized abuse” of animals (including crimes such as dogfighting and cockfighting) and the fourth area focuses on animal sexual abuse. The collection of data gained from such reports allows the FBI to “learn more about the correlation between animal cruelty and other crimes” (i.e. the Link) (National Sheriff’s Association, 2018, p.3).

Although the data collection being mandated by the FBI is a step in the right direction, it is clear that training programs and certifications need to be better implemented in order to make substantial progress. Currently, the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) is working in conjunction with the National Sheriff’s Association to offer free training courses crimes to law enforcement, animal control officers, humane investigators, code enforcement officers, veterinarians, and prosecutors. HSUS Law Enforcement Training Centers offer training courses on how to properly investigate dogfighting, cockfighting, and other animal cruelty crimes. According to the website of the National Sheriff’s Association, “In 2017 alone, the Center hosted more than 80 seminars, training nearly 4,000 officers across the United States”. In addition, the HSUS and the National Sheriff’s Association also work closely with the National Law Enforcement Center for Animal Abuse (NLECAA) to encourage the understanding of how animal abuse is linked to interpersonal violence. The increasing understanding of the Link by law enforcement officers allows for the crime of animal cruelty to be observed as a dangerous crime with a high potential of perpetuating further violence in society. It is important to note that although the HSUS Law Enforcement Training Centers are extremely progressive and beneficial for society, only 38 states in the U.S. have approved of such courses. Establishing the HSUS Law Enforcement Training Centers nationally, would exponentially increase awareness and understanding to protect all victims of abuse (National Sheriff’s Association, 2020).

Making Domestic Violence Shelters Better Sanctuaries for All Victims of Abuse

In addition to better educating veterinarians, human service professionals, and first responders on the Link, establishing a safe haven for all victims of abuse should be a top priority in society. As of 2018, only three percent of domestic violence shelters nationwide allowed pets within the shelter. This percentage is extremely horrifying when compared to the statistics presented by the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, which cites that seventy-one percent of domestic violence victims said their abuser threatened, harmed, or killed their companion animal. As a result of such disparities the American Veterinary Medical Association found that forty-eight percent of victims chose to remain in their abusive situations rather than escape the abuse they experienced without their pet (Kahler, 2018). As individuals began recognizing this specific obstacle that domestic violence victims faced, various animal advocacy groups began fighting to address the issue head-on.

In 2013, Purina (a widely known pet care company) began working with the Urban Resource Institute (URI) in New York City on its People and Animals Living Safely Program (PALS). The URI created the PALS program in 2012 to establish safe places where survivors of abuse and their pets could safely recover. Since the collaboration between Purina and the URI, existing apartments in URI shelters have been transformed to accommodate companion animals. Nathan Fields, the URI president and CEO, stated, “As recently as 2012, none of New York City’s 50 emergency shelters or tier-two shelters allowed survivors of domestic violence to bring their pets.” In October 2018, the URI opened a seven-story domestic violence shelter in Brooklyn called “PALS Place”. PALS Place was specifically designed to accommodate “family and pet co-living.” Today, the PALS program has established several emergency shelters in New York City, two in Manhattan and a “two-tier shelter” in Brooklyn, all of which accept pets. In addition, the PALS program also recognizes that victims of domestic violence often flee abruptly, so Purina supplies victims with supplies to care for their pets. The PALS program was so successful and innovative that the program began working with government officials to establish legislative protections for the victims of abuse and their animals (Kahler, 2018).

Creating Strong Advocacy Networks

Megan Brinster recognizes that establishment of advocacy networks between animal shelters and refuges helps ensure the safety and welfare of companion animals. Although shelters and refuges recognize advocacy networks, little support is provided by states. This issue becomes highly problematic in state-regulated animal shelters. For example, New Jersey currently has no statewide reporting system for animal abuse and neglect cases. Unless the information is supplied in public records, shelters have no way of knowing whether or not an individual attempting to adopt an animal has a history of animal cruelty (Brinster, 2020). This creates a significant obstacle for shelters as they assume responsibility for acting in the best interest of the companion animals under their protection. Acknowledging that there is a critical need for states to enact a statewide reporting system is a significant step for the prevention of companion animals falling back into the hands of their abusers. Recognizing the importance and expanding the reach of advocacy networks with other professional fields can save the lives of numerous abuse victims.

By adjusting how society addresses the crime of animal cruelty and filling the gaps in flawed protections, the violence that arises from such abuse can stand to a standstill. When multiple professions adequately address animal abuse, humans and animals are better protected. By better-educating veterinarians, clinicians, human service professionals, first responders, and prosecutors, the strongholds that victims desperately need can quickly be universally established. Awareness, education, training, and reform are crucial areas of focus that will allow for the crime of animal cruelty to be nationally acknowledged so proper protection can be established for muzzled victims. The next section of this paper will discuss the various policies and legislation encompassing protections for companion animals. In addition, the last section of this paper will discuss the idea of providing victims of animal abuse the right to legal guardianship, more specifically, guardian ad litems.

Protection Established Through Policy and Reform

The victims that animal advocates represent possess no socioeconomic power, no political clout, no voice to express their torment, and no means to participate in their own movement. They also do not possess the capacity to assert their historical significance to our society. And they are significant. Whether or not we believe they have rights, animals are central to our lives, past and present.

– Diane Beers

Legislation regarding the rights of companion animals is evolving and slowly becoming more progressive. As more individuals confront the Link, legislation regarding companion animals has transformed from preventative to proactive. Laws that once solely prohibited depictions of animal cruelty now work with the Link and extend stronger protections to animals and humans alike. Although progress has been made, our legal system still defines companion animals as the property of persons. Defining animals as property has severely limited and impaired the legal protections that our legal system extends to nonhumans. Establishing a means to which companion animals can be provided legal representation not only allows stronger protections but also aids in obtaining justice for abused animals.

The First Steps of Progress in Legislation

In 1999, the United States Congress reacted to a growing popularity within the fetish video industry known as “crush videos”. Crush videos featured women wearing high heels, being filmed from the waist down, “grinding” small animals to death under their feet. The United States Congress passed 18 U.S.C. § 48 in efforts to damage the growing market for such horrific videos. The bill illegalized the “visual and auditory depictions of animals being intentionally mutilated, tortured, wounded, or killed.” The bill also criminalized the distribution of such material as such conduct would violate federal and state laws where “the creation, sale, or possession [of such material] takes place.” Additionally, the bill defined that any depictions that possessed “serious religious, political, scientific, educational, journalistic, historical, or artistic value” were exempt from the criminalization set forth by 18 U.S.C. § 48. When President Bill Clinton signed the bill into effect there was a serious concern regarding its ambiguous language. The concern centralized around the broad language possessing the ability to be applied to other expressions of animal cruelty. In reaction to this, President Clinton declared that “the executive branch would only interpret the law as to cover depictions of ‘wanton cruelty to animals designed to appeal to a prurient interest in sex” (1999, 2558). It is imperative to recognize that 18 U.S.C. § 48 indirectly acknowledged the presence of the Link in the depictions of crush videos. Crush videos made substantial profit off the depictions of a women committing the act of animal cruelty. Not only was the crush video market thriving off the violent images of both female and animal bodies, the market was commoditizing animal abuse. In feminist literature, a prevalent form of battery occurs when batterers force their female victims to abuse their companion animals (Adams and Donovan 1995, 59). The government recognized that crush videos were ultimately publicizing this form of battery as a “fetish” and recognized that such depictions needed regulation. During the presidency of George W. Bush, the Department of Justice attempted to expand the reach of 18 U.S.C. § 48 and add further protections on the depictions of animal cruelty (Cassuto 2012, 12-19).

In 2004, the case U.S. v. Stevens was argued through various court circuits. Robert J. Stevens was indicted for violating 18 U.S.C. § 48 by distributing various dog fighting videos (Duignan n.d.). In 2008, the U.S. Court of Appeals found 18 U.S.C. § 48 to be “facially” unconstitutional as it violated Stevens first amendment rights. In 2010, The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari to the case and decided that 18 U.S.C. § 48 was in fact unconstitutional on different grounds (2010). The Supreme Court found that 18 U.S.C. § 48 was severely overbroad but encouraged congress to pass a more specific law targeting crush videos. Following the ruling, Congress enacted H.R. 5566, also known as the Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act of 2010, that was signed into effect by President Barack Obama. The Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act was aimed directly at defining crush videos as “obscene” which in turn, curtailed the First Amendment’s protections (Cassuto 2012, 12-19). Although U.S. v. Stevens did not directly deal with the act of animal cruelty as a crime, the Court still made strides questioning the level of compelling state interest in preventing animal cruelty.

Essentially, Congress originally passed 18 U.S.C. § 48 to prevent animal cruelty by outlawing its depiction and damaging its marketing. Congress recognized that the abuse of smaller companion animals was being commoditized by the fetish video industry. In order to protect animals from the acts of cruelty that were inflicted upon them ultimately required illegalizing the products and diminishing the market for the videos. The argument that Congress followed to pass the Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act possessed an important framework regarding the passage of legislation against the act of animal cruelty. Congress recognized that neither “expression nor the acts depicted contained any social value”, so it therefore had the authority to criminalize them. The First Amendment’s protections of speech however, can only be overridden “if the restriction is necessary to further a compelling state interest.” Essentially, for Congress to ban the content of the crush videos it faced the burden of proving that the ban was both urgent and necessary (Cassuto 2012, 12-19). The connection that is important to recognize within this paper is that Congress would have possessed a compelling state interest to ban the act of animal cruelty itself by recognizing the existence of the Link. The Link is a phenomenon that propels and cycles violence throughout society. In addition, the Link displays the vulnerability of numerous disenfranchised bodies falling under siege of abuse. It is evident that a strong argument could have easily been established in 2010 arguing that it was in fact a compelling interest of the government to federally prohibit animal cruelty as it would prevent both present and future violence in society. Unfortunately, in 2010 much of the research being conducted on the Link was not as well-known and widespread as it should have been.

Pet and Women Safety Act

In 2017, Congress made significant strides in legislation to improve federal protections of domestic and animal abuse victims. In 2017, significant strides in the legislation were created by Congress to improve federal protections of domestic and animal abuse victims. The Pet and Women Safety (PAWS) Act was established by recognizing the connections of abuse that correspond with the Link. The PAWS Act, also known as H.R. 909, was enacted to “amend federal criminal code to broaden the definition of stalking to include conduct that causes a person to experience a reasonable fear of death or serious bodily injury to his or her pet” (HR 909, 2017). In addition, the PAWS Act also included a clause on interstate violations of protective orders. Essentially if an abuser partakes in interstate travel, with the intent to violate a protection order against a pet that is included within the scope of such protective order, the abuser can face up to a five-year prison sentence, a fine, or even both. The abuser is also required to pay their victim, mandatory restitution for their losses, including any medical bill obtained for veterinary services of their companion animal. The PAWS Act directly appointed the Department of Agriculture to award grants to victims of domestic abuse with pets for sheltering, housing assistance, and support services. Lastly, the PAWS Acts conveyed “the sense of Congress that state should include, in domestic violence protection orders, protections against violence or threats against a person’s pet” (HR 909, 2017). On December 20, 2018, President Donald Trump signed the PAWS Act into law as a part of the 2018 Farm Bill. As stated by Representative Katherine Clark of Massachusetts and the bill’s co-sponsor, “No one should have to make the choice between finding safety and staying in a violent situation to protect their pet” (Grinberg 2018). The enactment of the PAWS Act displayed immense progress in terms of realizing the connections between domestic abuse and animal abuse. Congress was attempting to enact specific legislation regarding the Link that protects both human and animal victims of abuse.

Animal Cruelty as a Federal Felony

In 2019, Congress combined the legal framework set forth by the Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act of 2010 and the Pets and Women Safety Act of 2018 to establish a stronger penalty against animal abusers. The Prevention of Animal Cruelty and Torture (PACT) Act, also known as H.R. 724, was signed into effect on November 25, 2020. Congress recognized that Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act of 2010 did not directly address the actual acts of animal cruelty being depicted by the horrific videos. In addition, Congress also recognized that acts of animal abuse can occur outside of the protections of state cruelty laws (Animal Welfare Institute N.D.). The PACT Act added new provisions to the Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act of 2010 which criminalized the actual act of intentionally crushing an animal. violators of the Act would be subject to a prison term up to seven years and/ or a generous fine. The PACT Act also listed exemptions to its protections stating that such “conduct, or a video of conduct” are exempt if the acts are conducted for “(1) medical or scientific research, (2) necessary to protect the life or property of a person, (3) performed as part of euthanizing an animal, or (4) unintentional” (H.R 724, 2019). The main purpose of the PACT Act was to close the “loopholes” preventing punishment for animal abusers. The PACT Act created federal jurisdictions against the heinous acts of animal cruelty that possess and “interstate nexus.” Under its legislation, the PACT Act extends federal jurisdictions to “certain heinous and unspeakable acts of abuse” (Animal Welfare Institute N.D.). Although the acts listed above all make significant strides to protect companion animals against abuse we must ask ourselves if such protections are enough to safeguard humans and animals alike. Without the right to legal representation abused animals possess little to no agency or recourse forcing them to suffer as muzzled victims.

Legal Guardianship for Companion Animals

The recognition of animals as entities that deserve legal representation and autonomy is necessary for better protection. The first step in providing stronger protections for companion animals rests with resolving the dichotomies between ownership and guardianship. Ownership implies that a companion animal is property and has no autonomy. On the other hand, guardianship implies that the animals are “separate and unique entities deserving of protection and respect” (ASPCA, n.d). When an owner acknowledges themselves as a guardian of their companion animal, they are recognizing and acting in the best interest of the animal. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) states

In turn our relationship with the animal becomes one of a “caretaker”, whose sole responsibility is to protect and nurture the animal, rather than an “owner”, who has title to and dominion over the animal for the owner’s enjoyment and benefit as he/she sees fit ((ASPCA, n.d).

The concept of law guardians (guardian ad litems) is not new. Family court proceedings in many states include provision for law guardians to legally represent minors or “legally incompetent” individuals, referred to as “wards”. They are appointed by the court to protect and be legal representatives for individuals who are unable to properly advocate for their best interests. Under the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, states are required to appoint law guardians for children involved in abuse and neglect proceedings (Legal Information Institute, n.d). An argument can be made that companion animals should be considered under the list of wards of law guardians. Since companion animals, like some child abuse victims, cannot convey to authorities the abuse and neglect they experience, they are forced to suffer as silent victims.

Furthermore, in our current legal system, there are ways in which nonhuman animals have legal standing and can enforce their statutory rights through guardianships. Marguerite Hogan in her essay A Guardianship Model for Nonhuman Animals claims

With court approval, animal advocacy organizations may bring suit on behalf of nonhuman animals in the same way court appointed guardians bring suit on behalf of mentally challenged humans who possess an enforceable right but lack the ability to enforce it themselves. (Hogan 2007, 517).

The appointment of law guardians to companion animals will allow for the animal’s best interest to be heard, but this does not necessarily mean that the guardians have to be court appointed. Christopher D. Stone, in his seminal essay Should Trees Have Standing? -Toward Legal Rights of Natural Objects, recognized the challenges of seeking legal standing for “speechless entities”. Stone explained that one of the main obstacles in asserting the rights of nonhuman animals dealt directly with identifying a proper spokesperson for the entity’s cause. However, Stone claimed that this is not unusual as other “speechless and nonhuman entities” such as corporation, estates, municipalities, and ships possess legal standing to bring suit on their own behalf with the American legal system. (Stone, 1972). In Sierra Club v Morton, Justice Douglas in his dissent opinion, drew on Stone’s essay to affirm standing. Justice Douglas opined

The critical question of ‘standing’ would be simplified and also put neatly in focus if we fashioned a federal rule that allowed environmental issues to be litigated before federal agencies or federal courts in the name of the inanimate object about to be despoiled, defaced, or invaded by roads and bulldozers and where injury is the subject of public outrage. Contemporary public concern for protecting nature’s ecological equilibrium should lead to the conferral of standing upon environmental objects to sue for their own preservation. . . Inanimate objects are sometimes parties in litigation. A ship has a legal personality, a fiction found useful for maritime purposes. The corporation sole – a creature of ecclesiastical law – is an acceptable adversary and large fortunes ride on its cases. The ordinary corporation is a ‘person’ for purposes of the adjudicatory processes, whether it represents proprietary, spiritual, aesthetic, or charitable causes. So it should be as respects valleys, alpine meadows, rivers, lakes, estuaries, beaches, ridges, groves of trees, swampland, or even air that feels the destructive pressures of modern technology and modern life (1972, 742-743)

In his dissent, Justice Douglas proposed that organizations can bring suit as either a “guardian ad litem or as an organizational plaintiff in its own right.” Justice Douglas relied heavily on Stone’s standing model and argued that the Court should in fact recognize the concept of an environmental representative comparable to a “guardian ad litem, conservator, and receiver” (Hogan 2007, 529-532). The opinions within the 1985 court case Animal Lovers Volunteer Association (ALVA) v. Weinberg suggested that standing for nonhuman individuals could in fact be possible. In this suit against the United States Navy for shooting feral goats on the San Clemente Island in California, the court relied heavily on the dissents of Justice Douglas and Blackmun in Sierra Club v. Morton to recognize standing. While the Court ruled against ALVA, it claimed that a party has standing to protest an action taken by someone else if he or she can show two things-“injury in fact” arising from the action and injury “arguably within the zone of interests to be protected” by a violated statute (1985).

Although the Court determined the ALVA lacked legal standing to represent the feral goats, as it could not show the injury suffered by its members, it did propose a critical framework within its opinions. The court’s final decision aligned directly with Justice Douglas and Justice Blackmun’s dissents. The court concluded that an organization must have an “established history of dedication to the cause” of the nonhuman animal they are representing in order to obtain standing. ALVA was not considered a proper plaintiff in the matter as the organization could not provide proof of a history of advocating for the goats. The court did however state an organization who possessed a significant history of advocating for the cause of nonhuman animals could in fact bring suit “in the form of court-sanctioned guardianship” (Hogan 2007, 518). Thus, in a modern context, organizations such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), or even on a more local level the Ramapo-Bergen Animal Refuge could represent companion animals in a court of law.

It is necessary for the legal system to recognize that awarding standing for organizations to represent abused companion animals possesses compelling reasons. Animals are sentient beings that possess the ability to feel and respond to their surroundings. Unlike corporations and ships, animals can experience pain, torture, and suffering. Due to the fact that animals possess such qualitative differences from other inanimate objects that are already awarded legal standing, the court must recognize that animals do in fact deserve a stronger level of legal protections. In order to assert one’s standing an individual or in this case, a nonhuman animal, must meet the following standards: (1) injury-in-fact that is (2) fairly traceable to the defendant’s action and (3) redressable by a favorable court decision. It is clear that in animal cruelty cases, the victim of animal abuse does in fact meet the court’s standards to assert standing as a plaintiff. As stated within A Guardianship Model for Nonhuman Animals, “Since nonhuman animals are property and lack legal personhood, courts view their injuries as “tangential” to the true injury- that injury suffered by the person or organization bringing the suit” (Hogan 2007, 522). It is absolutely appalling that inanimate objects possess more rights under the American legal system than animals do. Just as their human counterparts, companion animals deserve the same merit of protection from the abuses that causes their intentional suffering. We as individuals must recognize that supporting the allowance of animal rights organizations to represent abused companion animals in a court of law in the form of a law guardian protects humans and animals alike. Confronting the Link and pursuing justice for abused animals will also provide justice for other muzzled victims within a home (and vice versa) (Hogan 2007, 518-523).

Conclusion

We have systematically failed companion animals. The practices to protect companion animals from abuse are simply not enough. Substantively, we need a change in our way of thinking about animal rights and recognize the existence of the Link along with establishing stronger preventive and punitive means to prevent animal abuse. It is imperative that we address the problem of patriarchal culture. The fight against the Link will establish a network of protectors for muzzled victims.