- About Ramapo

- Academics

- Admissions & Aid

- Student Life

- Athletics

- Alumni

- Arts & Community

- Quick Links

- Apply

- Visit

- Give

Sexual Assault on College Campuses: Feeding a Culture of Dismissal

(PDF) (DOC) (JPG)June 15, 2017

Molly Hopkins[1]

College – the golden years, the time to truly enjoy your youth, and unlimited access to alcohol. Living on college campuses is appealing to many students for these reasons. However, dormitories, apartments, and off-campus houses all provide a private space for sexual assaults to occur. This paper explores why college students are susceptible to sexual assaults and how campus culture perpetuates rape culture. I carried out primary research for this paper to examine the college campus culture surrounding sexual assault victims and perpetrators. Although there are regulations in place to safeguard gender equality, such as Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, there are many flaws. I will also address the limitations of these federal guidelines.

The roles college administrators and law enforcement play in the effort to prevent sexual assault encounters differ. For instance, universities cannot imprison those found guilty of sexual assault. For this reason, along with the fear of receiving underserved backlash for reporting their attacker, many college victims do not report their attackers and as a result, justice is being denied to these individuals. Finally, the paper will inspect the policies and procedures of sexual assault at Ramapo College of New Jersey. Utilizing national data with a focus on the microcosm of Ramapo, this paper aims to develop an understanding of the nature of sexual assault at educational institutions. College campuses foster a dismissive culture towards sexual assault that needs to be brought to light.

Title IX’s intent and limitations

Title IX was created to advance gender equality within education, particularly athletic opportunities for female students. However, the progress women have made under Title IX falls far short of gender equity. From the start, the implementation of Title IX has been subverted. “Congress enacted Title IX to prohibit sex discrimination in any education program or activity — public or private — receiving federal funds. The Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) is the primary federal agency responsible for enforcing Title IX, and it has developed regulations that require education programs to take steps to prevent and address sex discrimination” (The American Association of University Women, AAUW).[2] Soon after Title IX passed in 1972, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and high school administrators complained that boys’ sports would suffer if girls’ sports had to be funded equally. Regulations about how to implement the law were not released until two years later, and these regulations did not go into effect until July 1975 (Feminist Majority, 2014). Even then, OCR did not enforce the law and as a result, few complaints were investigated and resolved.

Title IX is known for prohibiting sex discrimination through equality in athletic programs that receive federal funding. One form of sex discrimination is sexual harassment, which is defined as “unwelcomed sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature that tends to create a hostile or offensive work environment” (Burton’s Legal Thesaurus, 2007). However, it covers much more than this. Many people have never heard of Title IX. Those who do know about Title IX think it applies only to sports, but athletics is only one of ten key areas addressed by the law. These key areas include: “Access to Higher Education, Career Education, Education for Pregnant and Parenting Students, Employment, Learning Environment, Math and Science, Sexual Harassment, Standardized Testing and Technology” (Title IX, 2015).[3] Since its passing 35 years ago, Title IX has been the subject of over 20 proposed amendments, reviews, Supreme Court cases and other political actions. All of these attempts to change the law clearly show that its purpose of gender equity has not been met. Thousands of schools across the country are not in compliance with the law (Title IX, 2015). The lack of effective legislation is expressive of an overall dismissive, gendered society.

One major limitation of Title IX is its lack of coverage. It is only applicable to institutions that receive federal funding or grant money. In 1984, Grove City College v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 gutted Title IX. Grove City College, a private, coeducational liberal arts school, sought to preserve its institutional autonomy by consistently refusing state and federal financial assistance. The college did, however, enroll a large number of students who received Basic Educational Opportunity Grants (BEOG’s) through a Department of Education-run program (465 U.S. 555). The DOE concluded that this assistance to students qualified the College as a recipient of federal assistance and made it subject to the nondiscrimination requirements of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. When the college refused to comply with the requirements, the DOE attempted to terminate assistance to the student financial aid program. The college challenged the DOE’s actions. The Court concluded that prohibiting discrimination as a condition for federal assistance did not infringe upon the First Amendment rights of the college and that the school was free to end its participation in the grant program. In that ruling, the court stated that Title IX did not cover entire educational institutions – only those programs directly receiving federal funds, setting limits on equality, and undermining the power of Title IX.

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 addresses sexual harassment, gender-based discrimination, and sexual violence. Sexual violence includes attempted or completed rape or sexual assault, as well as sexual harassment, stalking, voyeurism, exhibitionism, verbal or physical sexuality-based threats or abuse, and intimate partner violence (Bolger, 2015). Title IX protects everyone from sex-based discrimination, regardless of real or perceived sex. Schools have the responsibility to protect students and take necessary steps to foster a hospitable environment for all students. Title IX specifically states that: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance” (Title 20 U.S.C. Sections 1681-1688).

While Title IX clearly intends to promote gender equality, it misses the mark with its limitations. By only protecting students attending schools that receive federal funding, Title IX is inherently selective about who it is protecting. To better enforce Title IX in institutions it applies to, the U.S. Department of Education (ED) maintains an Office for Civil Rights. OCR’s responsibility is to ensure that institutions, which receive ED funds, comply with Title IX (US Department of Education, 2015). The primary enforcement activity is the investigation and resolution of complaints filed by persons alleging sex discrimination. Additionally, through agency-initiated reviews of selected recipients, OCR is able to identify and remedy sex discrimination, which may not be addressed through complaint investigations (US Department of Education, 2015).

Another limitation on Title IX’s effectiveness is the lack of oversight and enforcement. Although the system is set up to address complaints, there are a multitude of institutions under its jurisdiction, thus the OCR is unable to investigate and review the policies and practices of all institutions receiving ED financial assistance. OCR provides information and guidance to schools, universities and other agencies to assist them in voluntarily complying with the law (US Department of Education, 2015). By asking institutions to voluntarily comply with laws, the OCR is leaving ample opportunity for institutions to not comply or mishandle sensitive cases.

It is important to understand how to file a discrimination complaint with OCR. Anyone who believes there has been an act of discrimination on the basis of sex against any person or group in a program or activity, which receives ED financial assistance, may file a complaint under Title IX (US Department of Education, 2015). Therefore, the person filing the complaint does not need to be a victim of the alleged discrimination but may speak on behalf of another. This is significant because it allows the victim to be heard while still allowing them to be somewhat anonymous and comfortable in their environment. However, a complaint must be filed within 180 days of the date of the alleged discrimination (US Department of Education, 2015). Putting a limit on the time it takes for a person to come forward after being sexually discriminated against is a cause for concern. The desire for complaints to be timely is understandable, however victims may choose not to step forward and file a complaint until they feel comfortable, know what options are available, or realize they were wronged. The OCR should not put a time limit on someone’s ability to file for sexual discrimination. Justice should not be circumvented for expediency.

As mentioned before, Title IX covers sexual harassment, gender-based discrimination, and sexual violence. Sexual violence is broken down into sexual assault and sexual misconduct (or contact). Sexual assault is defined by the state of New Jersey as “penetration, no matter how slight, of the victim’s mouth, vagina, or rectum by a penis; or the insertion of a hand or object into the victim’s vagina or rectum, without the victim’s consent (including if the victim was unable to give consent due to incapacitation).” Criminal sexual contact is defined as “non-consensual touching of the victim’s breasts, genital area, buttocks, and thighs, or the forced touching of the actor’s genitals or breasts” (Ramapo College of New Jersey, 2015). By definition, criminal sexual contact happens at most college parties. Although the intent may not be malicious, aggressive dancing can be classified as non-consensual touching. Victims may not see an incident as important enough, nor can they provide concrete proof of the action. Therefore, even victims can add to the dismissive culture surrounding sexual assault.

Federal courts did not recognize sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination until the 1970s, because the problem was originally seen as isolated incidents of flirtation in the workplace. However, it is becoming clear that unsolicited sexual advances and remarks, mostly towards females, are indeed sex discrimination and they create an uncomfortable and hostile environment. The ambiguous nature of sexual encounters creates a burden for victims when trying to prove their encounter was nonconsensual. A surprising number of university policies never define consent. Many do say that they have zero tolerance for “non-consensual” sexual conduct. However, failing to provide a definition of consent leaves room for interpretation and an unclear understanding of what classifies as sexual assault. One school in particular that does a respectable job of removing any elusiveness from sexual conduct is Case Western Reserve University.

Case Western’s sexual assault policy includes a definition of consent:

“Consent is the equal approval, given freely, willingly, and knowingly of each participant to desired sexual involvement. Consent is an affirmative, conscious decision – indicated clearly by words or actions – to engage in mutually accepted sexual contact. A person forced to engage in sexual contact by force, threat of force, or coercion has not consented to contact. Lack of mutual consent is the crucial factor in any sexual assault. Consent CANNOT be given if a person’s ability to resist or consent is substantially impaired because of a mental or physical condition or if there is a significant age or perceived power differential. Examples include, but are not limited to being:

- unconscious,

- frightened,

- physically or psychologically pressured or forced,

- intimidated,

- substantially impaired because of a psychological health condition,

- substantially impaired because of voluntary intoxication, or substantially impaired because of the deceptive administering of any drug, intoxicant or controlled substance” (Case.edu)

No definition of consent is concrete due to the nature of sexual encounters. College students may feel uncomfortable in a situation but stay quiet out of embarrassment or fear. Silence does not constitute consent. This is why it is important that both parties verbally express interest in what they want to do. Consent is not reluctantly giving in to certain acts after being convinced. Consent is an expressed desire, whether verbal or physical, to perform a certain sexual act. The party and hookup culture of college campuses increase the ambiguity of sexual contact. Consent needs to be granted before there is sexual activity each and every time. When there is no consent, a sexual assault has occurred. This is why the actual number of sexual assaults is much higher than reported.

Just as a work environment can become hostile, so too can a classroom, dorm building, or team locker room. Title IX works to protect against and prevent sexual discrimination in education. A hostile environment can negatively affect a student’s ability to learn, feel safe, or even enjoy learning. Under Title IX guidelines, harassment is considered to be conduct that creates an impermissible hostile environment if it is “sufficiently serious that it interferes with or limits a student’s ability to participate in or benefit from the school’s program” (Campus Safety Magazine, 2015). Less severe conduct with ample repetition may ascend to this level, while even one incident that is more serious may rise to this level. For example, “a single instance of rape is sufficiently severe to create a hostile environment” according to OCR.

The harassing conduct may occur in any setting related to a school’s programs, including off-campus activities such as field trips, athletic events, or even school-recognized fraternity or sorority houses. While it may fall outside a school law enforcement agency’s jurisdiction, institutions have an obligation to respond to harassment complaints. This is especially true when it rises to the level of sexual violence that originally happened off campus or outside an educational program if a student experiences “the continuing effects of off-campus sexual harassment” in an educational setting (Campus Safety Magazine, 2015). An example of such a setting includes a victim continuing to encounter his or her assailant in classes, dining halls or residence buildings. When an institution addresses sexual violence, even if it occurred off-campus, it must do so using procedures that comply with Title IX guidelines.

College administrators must be proactive in ensuring that campus is free of sex discrimination. Everyone is covered under Title IX, including students that do not directly experience sex discrimination. Schools must take immediate steps to address any sex discrimination, sexual harassment, or sexual violence on campus to prevent it from affecting students further. If a school is aware of discrimination taking place it must act to eliminate it, remedy the harm caused, and prevent reoccurrence. Administration may not discourage survivors from continuing their education, such as recommending them to “take time off” or forcing them to quit a team, club, or class (Bolger, 2015). Students have the right to remain on campus and have every educational program and opportunity available to them.

Every school is required to have a Title IX Coordinator who handles complaints. The Coordinator’s contact information should be publicly accessible. It is crucial that schools follow these guidelines in order to create an easier process for victims to file complaints. Regardless if a student reports an incident to the police, the school must promptly investigate any complaints filed. The school should use a “preponderance of the evidence” standard to determine the outcome of a complaint, meaning discipline should result if it is more likely than not that discrimination, harassment and/or violence occurred (Bolger, 2015). The final decision should be provided to the victim/filer and the accused in writing. Both parties have the right to appeal the decision.

Schools must take instant action to ensure a victim can go on with their education without further sex discrimination, harassment, or violence. In addition to issuing a no contact order, reasonable changes to housing, class or sports schedule, campus job, or extracurricular clubs must ensure an education free from sex discrimination, harassment, or violence (Bolger, 2015). Schools have the right to create these arrangements even before a formal complaint, investigation, hearing, or final decision is made regarding a complaint. It also should continue after the process is over since each student has the right to an education free of sex-based discrimination. These accommodations should not burden the complainant-victims or limit their education in any way. Schools can require the accused to likewise change some school activities or classes to ensure there is not an ongoing hostile educational environment.

Colleges and universities are prohibited from retaliating against someone for filing a complaint. Schools must also keep a victim safe from other retaliatory harassment or behavior, including no contact directives. Any type of retaliation can and will be reported in a formal Title IX complaint to the U.S. Department of Education since everyone has the right to be free from a hostile educational environment (Bolger, 2015).

When cases involve sexual violence, schools are prohibited from encouraging or allowing mediation of the complaint. Every student has the right to a formal hearing. Title IX Guidance of 2011 prohibits schools from allowing mediation between an accused student and a complainant-victim in sexual violence cases only (Bolger, 2015). In sexual harassment and discrimination cases schools may still offer mediation as an option.

Although schools are discouraged from allowing the accused to question the complainant-victim during a hearing, they are not prohibited. Therefore, if a school allows such questioning, a student may wish to seek a legal advocate to file a Title IX complaint with the U.S. Department of Education about the school’s hearing process. Although schools should aim to make the process as comfortable as possible for victims, if the complainant does experience any hostile incidents or environment throughout the process, they should file in order to bring attention to the policy and procedure of the school.

Title IX also prohibits colleges from making a student complainant-victim pay the costs of reasonable accommodations that were required to continue an education free of sex-based discrimination, harassment, or violence (Bolger, 2015). If a student requires counseling, tutoring, housing changes, or any other reasonable remedies in order to continue a hostile-free education, the school should provide it all for no cost. Schools are also responsible for any failure to eliminate the discrimination, harassment, or violence, whether that is reimbursement of lost tuition or related costs. Academic institutions contain the heavy burden of ensuring each student’s safety and comfort. Universities are a playground of freedom and opportunity for all of their incoming students. While a fun atmosphere, college campuses also perpetuate a dangerous and dismissive environment.

Campus life generates gendered sexual spaces

Living on a college campus can be an exciting time for eighteen year olds. There are parties, newfound freedom from parents, and so many people of the same age in the same vicinity. However, all of these opportunities help to promote a gendered environment. With media applications such as YikYak, Instagram accounts that feature strangers making out, and fraternity parties that only charge males to enter, college environments consistently separate and exploit women. YikYak is an application that features text posts from anonymous people in a specific geographic region. It has become very popular at colleges and universities. Since anyone can generate a post with free range on what they want to say, the posts are usually vulgar, rude, and inappropriate. I have witnessed many homophobic, racial, sexist, and classist statements. One night in particular at Ramapo College I stumbled across YikYak posts that referenced Take Back the Night, a nation-wide event held at many colleges and universities that allows victims of abuse and sexual assault to speak out and take back the night. It starts with a very serious discussion of the issues, then calls for volunteers to share their own personal stories, and ends with a walk and chant around campus. There were numerous posts that promoted rape culture, victim-blamed, and even made sexual threats. These posts are public, which can be triggering for victims and reassuring for assailants.

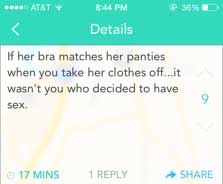

Despite the event’s purpose of uplifting victims and giving them a voice, YikYak gave a voice to hatred and disrespect of women. Included were various heinous comments such as “Rape doesn’t happen here,” “Shut up we don’t care about it. you probably lead him on anyway,” and “If her panties matched her bra… it wasn’t you who decided to have sex.”

The fact that at least nine individuals took the time to ‘up vote’ this post showcases the ignorance college students have towards sexual conduct.[4] It assumes that sex is normally a male decision and this instance is different because a female has ‘decided.’ It also confirms that rape culture is supported through social media. The post insinuates that women only dress for sex. Both parties should be consenting and deciding to have sex, or else it is sexual assault. How does wearing a matching bra and underwear equate to asking for sex? The thought process of the author of this post is misguided by the fallacy that females dress solely to please men.

These horrible comments embody a misogynistic, sexist, and gendered way of thinking and acting. In addition, at Ramapo College there was an Instagram account (that has since been deleted) entitled “Ramahookups” that posted pictures of random students hooking up at parties, in their dorms, and various places on campus. Anyone could have taken the picture and sent it directly to this Instagram to be posted by the creator on the account. Hundreds of students followed this account, ‘liked’ the pictures, and commented on them. The photographer and publisher of these photos clearly did not have permission from the people in these pictures.

The public exposure of intimate moments promoted an already present gendered atmosphere since the girls in the pictures were mocked and ridiculed while the boys were congratulated and respected by their peers. This type of sexual double standard already exists in society but is particularly evident in our young adult, college population. A gendered sexual space enhances a dismissive culture surrounding sexual assault. Having different standards regarding sexual encounters between males and females is echoed even further when sexual assault cases involve bystanders taking videos of the incident.

The structure of party life, particularly fraternities, at colleges also generates an enhanced gendered culture. Women are treated differently at parties even before they enter the door. Males are usually charged money to enter parties and women are usually let in for free. The expectation is that these women will hopefully continue to come back, binge drink, and sleep with them. By not charging women to drink, males believe women are indebted to them. There is an expectation of sexual favors and advances from the girls that these males ‘let into parties for free.’ Guys that have to pay to get into the party are paying not only for the alcohol, but also for the opportunity and expectation of talking to and hooking up with the girls inside. This type of interaction and sexual expectation between college males and females at parties constructs a gendered environment. The women are seen as prey and the men as hunters. The party structure enhances rape culture by assuming that women who drink automatically want to have sex. Open parties generate space for the victim-blaming mindset to be put into action. Many college males accept the false notion that women are at parties solely to please them.

Nearly one in four women will become a victim of sexual assault while attending college. In actuality, the number is higher, however less than 5-percent of completed or attempted rapes against college women were reported to law enforcement. Nine out of ten times these women know their rapist (Fisher et al, 2000). In most cases, the victim felt comfortable enough to tell a friend but not school officials. It is important to note that not all rape victims are female. However, in this paper I will be focusing on females as victims and males as perpetrators. It is also vital to point out that the college environment does not automatically result in sexual assault. However, the submissive college culture aids in a minority of individuals’ ability to perform such heinous acts.

Campus culture can confuse many young men and women on what actually constitutes sexual assault. College freshmen undergo a transition in their lives when moving away from home for the first time. This new experience is defined by coed dorms, near constant socializing that often involves alcohol, and the ability to retreat to a private room with no adult supervision (Neidig, 2009, p.181). Socialization into this different world can result in confusion on what sexual assault can be. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, “sexual assault is any type of sexual contact or behavior that occurs without the explicit consent of the recipient. Falling under the definition of sexual assault are sexual activities such as forced sexual intercourse, forcible sodomy, child molestation, incest, fondling, and attempted rape.”

One reason college sexual assault is extremely underreported may be due to a lack of proper knowledge of the definition. Women may think that because an act was not completed or because alcohol was involved, it does not constitute sexual assault. Any sort of unwanted or unsolicited sexual conduct is defined as sexual assault and should be treated as such. While most victims of rape know their perpetrators, the party culture of college generates a higher chance of ‘party rape.’ Although party rape may be classified as acquaintance rape in some circumstances, it is not uncommon for the woman to have had no prior interaction with the assailant, that is, for the assailant to be an in-network stranger (Armstrong et al, 2006, p. 484).

College campuses, especially larger institutions, produce an expectation of partying that fosters the development of sexualized peer cultures organized around status. Cultural expectations that partiers drink heavily and trust party-mates become problematic when combined with the expectation that women should be nice and defer to men (Armstrong et al, 2006, p. 484). When intoxicated, women become more vulnerable to sexual assault. This is due to men that exploit their lack of control in order to extract non-consensual sex. Unfortunately, rather than criticizing men’s behavior, victims are usually blamed for the outcome.

Alcohol consumption plays a role in the persistence of sexual assault of college females. However, there seems to be a cultural double standard regarding intoxication: if the rapist was drunk, it reduces his culpability, but if the victim was drunk, it increases her culpability (Kramer, 1994, p.115). Intoxicated women are viewed by our patriarchal society as promiscuous and desiring sex. This is merely a cultural myth. Additionally, women are seen as lacking the inclination or ability to express their sexual desires candidly. These false accusations become particularly dangerous when they pervade the social and legal interpretations of “consent” in the context of rape, particularly in alleged cases of “acquaintance rape” (Kramer, 1994, p.115). The victim blaming phrases of “she was asking for it,” “she didn’t say no,” and “she was dressed like that for a reason,” are all echoed when alcohol is involved. No person under the influence can legally consent to sex.

The majority of sexual assaults on campus take place at college parties where heavy binge drinking and the use of drugs are prevalent, which opens up ample opportunity for acquaintance rape. Seventy-five percent of men and fifty-five percent of women reported drinking or taking drugs prior to an attack (Kramer, 1994, p.116). Intoxication can lead to victims refusing to step forward out of fear, or lacking evidence due to having no recollection of the incident. College rapes are not a new epidemic. In a 1985 study of fifty college gang rapes, researchers found that every one of the cases involved alcohol (Kramer, 1994, p. 116). Although alcohol is a factor involved in acquaintance rape, it is clearly a power-driven crime. Intoxication makes it easier for rapists to control their victim. This is why college parties that involve heavy drinking are creating more opportunities for rapes to occur.

Many of these parties occur at off-campus fraternity houses. The separation of the party house from the campus further distances people from responsibility. As a sorority woman myself, I am aware of the organizations and individual members that do not act in such a problematic manner. However, fraternities as a subculture do in fact breed an unsafe environment for women and promote rape culture in many ways:

An analysis of the norms and dynamics of the social construction of fraternity brotherhood reveals the highly masculinist features of fraternity structure and process, including concern with a narrow, stereotypical conception of masculinity and heterosexuality; a preoccupation with loyalty, protection of the group, and secrecy; the use of alcohol as a weapon against women’s sexual reluctance; the pervasiveness of violence and physical force; and an obsession with competition, superiority, and dominance. Interfraternity rivalry and competition – particularly over members, intramural sports, and women – encourage fraternity men’s commodification of women (Martine and Hummer, 1989, p.457).

Research indicates that fraternities are vitally concerned with masculinity more than anything else. This means that they are constantly trying to prove their masculinity to themselves, other males, and females. “Valued members display, or are willing to go along with, a narrow conception of masculinity that stresses competition, athleticism, dominance, winning, conflict, wealth, material possessions, willingness to drink alcohol, and sexual prowess vis-à-vis women.” Assessing a pledge’s ability to talk to girls is, in part, a preoccupation with heterosexuality and a conscious avoidance of men who seem to have effeminate manners or qualities (Martine and Hummer, 1989, p.460). This subgroup of dominant masculinity generates a power structure that fraternity men use over others, primarily females.

Fraternities are also fixated on loyalty to their organization and each other. Members are expected to be eternally devoted to their brothers. This type of projected secrecy and protection generates a separation from brothers and non-brothers. Guaranteed group protection creates an easier opportunity to get away with sexual assault. Fraternity men often use alcohol as a weapon against sexual reluctance. One fraternity man described alcohol use to gain sex as follows: “There are girls that you know will fuck, then some you have to put some effort into it … You have to buy them drinks or find out if she’s drunk enough…” (Martine and Hummer, 1989, p.465). Young men such as this fraternity man consistently see women as prey. The mission of the night for many of the men is to get a woman to sleep with them, by any means necessary.

Violence and physical force also play a major role in the history of fraternities. Their record of hazing, fighting, property destruction, and rape has caused them problems with insurance companies. Fraternities are “the third riskiest property to insure behind toxic waste dumps and amusement parks” (Odem and Clay-Warner, 2003 p. 172). Due to this masculine and competitive nature, women are viewed as bait. Attractive women are routinely used to lure in pledges to join a certain fraternity. The implication is that these women will party with you and be by your side if you join the organization. Promising access to beautiful women as a status symbol to gain male membership exemplifies the twisted logic of misogyny. The women are merely being objectified and used as props for males in fraternities to gain superiority. This exploitation of women as sexual objects showcases the gendered campus environment.

Young males whose maturity and judgment are undeveloped solely occupy fraternity houses. Yet, “fraternity houses are private dwellings that are mostly off-limits to, and away from scrutiny of university and community representatives, with the result that fraternity house events seldom come to the attention of outsiders. Practices associated with the social construction of fraternity brotherhood emphasize a macho conception of men and masculinity, a narrow, stereotyped conception of women and femininity, and the treatment of women as commodities. Contributing factors to coercive sexual relations and the cover-up of rapes include excessive alcohol use, competitiveness, and normative support for deviance and secrecy” (Martine and Hummer, 1989, p.469).

Socialization in a patriarchal society that lacks extensive sanctions for abusing women presents male peer groups with false rationalizations that helps justify the abuse: the heavy use of alcohol, a narrow conception of masculinity, group secrecy, and the sexual objectification of women (Schwartz and DeKeseredy, 1998, p. 601). This structure of projected masculinity is also a cause for concern with collegiate athletes. There have been countless cases of rapes committed by star athletes that are very rarely followed through or punished. The male-dominated field of collegiate sports refuses to believe their star athletes can do wrong and have even gone as far as to demonize the victims who speak up.

One case currently in the limelight is that of former Florida State University quarterback Jameis Winston. Back in 2013 Winston was not charged with or convicted of a crime after being publicly investigated for raping a fellow student. However, there were serious questions about the responsiveness and thoroughness of the Tallahassee Police Department. Erica Kinsman, the former female student that is now publicly telling her story in a documentary, has just filed a lawsuit against him. Since the burden of proof in a civil lawsuit is much lower than in a criminal case, Kinsman could have a better chance of winning a jury verdict if it goes to trial.

Winston has denied the charges against him and has gone so far as to say that “The only thing as vicious as rape is falsely accusing someone of rape” (ESPN Go, 2014). It is not unusual for accused rapists to go on the offensive and claim victimization. While it is clear that being falsely accused of rape is a horrible thing to endure, it very rarely happens. Statistically, between 2-percent and 8-percent of reported rapes are found to be false (NSVRC, 2009) (it is important to remember that only about 40-percent of rapes are reported). The equivalence between rape and false rape accusations is false. One is a pervasive social problem that affects millions, while the other is a freak occurrence (Roberts, 2014). Not only in general is this severely misguided, but especially in instances where there is an evident power structure. Despite the allegations, he has won the most coveted college football award, the Heisman trophy. He also just landed the spot of the number one pick for the NFL Draft.

Big-time athletes at the collegiate and professional level time after time commit crimes and are merely scolded or slapped on the wrist. Sometimes they are even supported more than the victim. This social structure reinforces a dismissive attitude towards the actual victims. The consequences of being an athlete’s victim are significant. Lizzy Seeberg was a 19-year-old college freshman when she claimed to have been assaulted by a Notre Dame football player. Ten days later, after a series of threatening messages from a friend of the player, and coming to the realization that the player would not face justice, she killed herself (St. Clair and Lighty, 2010). Although her tragic case drew more attention than most, she’s hardly unique. A third of rape victims contemplate suicide, and 13-percent will actually attempt it (Kilpatrick et al, 1992, p. 7). Young female victims see other victims step forward and get nothing in return but public ridicule and threats.

Victims such as Lizzy are fearful of being attacked and ostracized by their campus community due to a deeply engrained idea of college sexual expectations. One example of the ongoing rape culture on college campuses is what happened to Carolyn Luby at the University of Connecticut. Having attended UConn for a full year of school, I had firsthand experience with the obsession involving athletics. Luby, a rape survivor, wrote an open letter to President Susan Herbst after UConn unveiled a new husky logo and a revamped image. In the letter she addresses the administration’s lack of punishment of male athletes that have committed crimes on campus. She writes about a male athletic peer culture that has taken over her campus and notes her concerns regarding the aggressive nature of the new logo:

Instead of giving these problematic aspects of male athletic peer culture at UConn a second look or a giving the real face of athletics a true makeover, it appears that the focus of your administration is prioritizing the remodeling of the fictional face of the Husky Logo. Instead of communicating a zero tolerance atmosphere for this kind of behavior, increasing or vocalizing support to violence against women prevention efforts on campus in the face of such events, or increasing support to student run programs that seek to work with athletes on issues of violence as well as academic issues, it would appear that your administration is more interested in fostering consumerism and corporatization than education and community (Luby, 2013).

Luby is making these arguments in reference to incidents involving male basketball players who received little to no punishment for their actions. On October 6th 2012, Lyle McCombs was arrested on charges of second degree breach of peace for a domestic violence dispute in which he was “yelling, pushing, and spitting at his girlfriend” during an argument outside a residence hall. On February 11th 2013, Enosch Wolf was arrested on charges of third degree burglary, first degree criminal trespassing and disorderly conduct when he “refused to leave” a female student’s apartment, “grabbed the hair of the victim and pushed her head” and “knocked the glasses off the victim’s face with his hand”. On March 21st 2013, Tyler Olander was arrested for trespassing in a structure or conveyance while on Spring Break in Panama City, Florida (Luby, 2013).

The only student that was reprimanded by the administration was Wolf. This was due to head coach Kevin Ollie taking it upon himself to kick Wolf off the team. The other men were not punished via the school or athletic department for their actions. Playing a sport in college should be viewed as a privilege that can be taken away. The school calculated their athletic ability to be more important than the victim’s ability to seek justice and feel safe. UConn, famous for their basketball program, forced the victims to see their perpetrators getting cheered on, displayed on posters throughout campus, and nationally televised during games. The school is protecting perpetrators of assault by allowing them to continue their academic and athletic career as if nothing happened. Not punishing perpetrators of assault against women blatantly shows acceptance of gender-violence, which extends to sexual assault. In both domestic violence and sexual assault, power is a key element in the attackers’ reasoning.

Luby received heavy backlash for publishing her feelings regarding the way the administration’s decisions were affecting her. A website called Barstool Sports reprinted Luby’s letter, which generated violent, gender-based comments. A second site was created just so people could make rape jokes about her. On campus people were harassing her and even Rush Limbaugh weighed in to mock her, going as far as to call her a “feminazi” (Chemaly, 2013). These types of jokes that trivialize sexual assault encompass rape culture and the harm it can have on victims. Joking about rape diminishes the seriousness of the crime and the feelings of victims are compromised. Luby’s peers, administration, and most of the country dismissed her letter. Luby made valid arguments, which were downplayed by the severe and unjust backlash she received.

UConn is not the only school with male athletes who are getting away with assaults on women. While male student athletes make up “3.3-percent of the U.S. college population, they’re responsible for 19-percent of sexual assaults and 37-percent of domestic violence cases on college campuses” (Chemaly, 2013b). The assaults do not have to be sexual in order to contribute to a violent gendered culture. The dismissive response by administration, peers, and law enforcement safeguards athletes’ ability to continue their careers without punishment. College football players, such as Winston, continually avoid punishment due to their status.

Syracuse guard Eric Devendorf hit a female student in November 2008 and initially was suspended for the rest of the 2008-09 academic year. That suspension was reduced to 40 hours of community service, enabling him to play the entire Big East season. His athletic career was not altered in any way. In the fall of 2010, Tony Woods, a center on Wake Forest’s basketball team, was arrested and charged with assaulting his girlfriend, reportedly fracturing her spine. He received a 60-day suspended prison sentence. This type of violence is inexcusable and warrants a harsher punishment. There is a pattern of college athletes violating female students’ human rights. Baylor basketball player LaceDarius Dunn reportedly broke the jaw of his girlfriend in the fall of 2010. She asked that the charges be dropped, and a grand jury declined to indict him (Lapchick, 2011).

It is not uncommon for the victim of assault to drop charges for fear of additional violence from the aggressor and public scrutiny. The same is true for victims of rape. Many times high profile cases end in plea agreements. Florida State University’s wide receiver Chris Rainey was charged with stalking after sending threatening text messages to his girlfriend in 2010. He reached a plea agreement with authorities and stayed out of court. Then-coach Urban Meyer suspended him for five games. There are countless examples of college male athletes endangering their female peers. Punishments are not harsh enough, nor do they address the issue at hand. By refusing to take a punitive approach, universities are perpetuating the trivialization of assault. The nation was shocked and devastated by Jerry Sandusky’s actions.[5] He was publicly scrutinized and a large-scale investigation took the nation by storm. He was sentenced to 30 to 60 years behind bars. Why do we not hold sexual predators of women and girls equally responsible? Gender-based violence against young women is not treated the same.

Society views girls differently. Campus culture presumes that all females desire sex. It is believed that all students are having random hookups and it is a natural part of college. Rape culture is perpetuated every time a victim steps forward and is not believed or supported. Fraternity parties, dorms, and a freeing environment increase opportunities for hookups to occur. However, not all of these are consensual, particularly when alcohol is involved and action needs to be taken when victims step forward. Campus culture is inherently gendered but is enhanced by programming and opportunities that differ for those that identify as males and females.

Ramapo College

In August 2014, Ramapo College of New Jersey held a presentation to Peer Facilitators entitled “Haven – Understanding Sexual Assault” led by Corey Rosenkranz, coordinator of Substance Abuse & Violence Prevention. The presentation was implemented to inform new and returning peer facilitators about the choices first-year students make in relation to alcohol. During the program, Rosenkranz said female students needed to be self-aware about actions that could invite sexual assault (French and Garcia, 2014). She included how women dress, how they interact socially, how much they drink, and how their body language and facial expressions could be interpreted. “The use of victim-blaming in teaching sexual assault prevention places the burden of prevention on the targets of sexual assault and creates a culture in which survivors are shamed, perpetrators are excused and society is given no responsibility to end the pandemic” (French and Garcia, 2014).

Victim blaming taught at a collegiate level is inexcusable. “When you’re constantly told that it was something you wore, your facial expression or because you were drinking, you start to convince yourself that maybe it really was your fault,” said Kaitlyn Maglione, administrative assistant at Healing Space. This is harmful to victims, future victims, and the public at large. It is blaming women for existing. Telling college students that subtle movements could invite others to rape them is ignorant and detrimental to victims. It is essentially dismissing the perpetrator’s responsibility for the crime.

The college received a lot of backlash from the student body, professors, alumni, and media outlets. After a few months, Ramapo students were arrested for an alleged rape of an intoxicated first year female student in a dorm room. The college took a gendered approach to teaching about sexual assault after the assault. Ramapo Public Safety held a Rape Aggression Defense (R.A.D.) class offered only to female students and female faculty members this past fall semester. There are a number of problems with this program. Only offering a self-defense training class to women is offensive to male victims and assumes that all victims are females. It is promoting rape culture by insisting that women are responsible for fighting off attackers rather than placing blame on rapists. Although it can be helpful for females to know how to protect themselves, the timing of the R.A.D. classes make it seem as though the female victim could have and should have taken steps to avoid being raped.

By segregating the female population of Ramapo College, a gendered environment is further developed. It is clear that the female population is unsafe if Public Safety feels the need to produce this program. Rather than teaching females how to avoid situations in which they can be raped, schools should be actively teaching against sexual assault. Many times perpetrators do not think they are doing anything wrong. Educating students about sexual assault can be beneficial for both males and females. Educational institutions focus too heavily on what females are wearing, what they are drinking, and whom they are with, rather than holding males accountable for their actions.

Additionally, most institutions care more about their public relations being tarnished than how victims feel. This can be seen in Ramapo College’s handling of the alleged rape. The administration found a scapegoat in alcohol. Placing the blame on drinking and cracking down on fines for alcohol takes away the responsibility of perpetrators and partially blames the victim. There was a policy change in alcohol and party fines shortly after the incident, overshadowing the main assault and taking away from its seriousness. The focus on drinking makes it seem as though alcohol is the sole reason for sexual assaults. Most sexual assaults are actually committed by someone the victim knows in their own house (RAINN, 2009). Ramapo made it look as though they are taking steps to address the problem, but the real problem was not addressed and is routinely ignored nationwide.

Classroom or courtroom

There are plenty of professional athletes that have amazing careers after allegations of sexual assault were either proven, or at least not proven to be false. Mike Tyson was convicted of rape and was welcomed with open arms back into the world of boxing after serving some time in prison. ESPN tweeted him birthday wishes and he has been given roles in movies including The Hangover. Kobe Bryant settled out of court with his accuser and did not miss any playing time. He still managed to earn $31 million in endorsements in 2013 (Roberts, 2014). Ben Roethlisberger was suspended a few games after repeated allegations of sexual assault. Time and time again, athletic talent has trumped accusations of rape. These men have been deemed more valuable than their victims. It is apparent that if you are a man, you have money, and people seem to generally like you, then nothing, including raping another human being will get in the way of your life or career.

While it is unknown if Jameis Winston is guilty or not (and he was cleared of violating the student code of conduct), the statistics suggest he almost certainly is, since the false accusation rate is only 2-8-percent (NSVRC, 2009). Yet, even if he were to be found guilty, there is no chance he will go to jail, as there is less than a ten-percent chance that he would serve a day in jail (NSVRC, 2009). Only three out of 100 rapists serve so much as one day in prison (Lee, 2014).[6] This is especially true for rapists that are found guilty through school administration, who have zero-percent chance of being imprisoned. These statistics represent the dismal chances victims have of reaching justice. Not only are victims habitually dismissed, but also when their case is pursued, the odds of seeing their rapist behind bars are slim. This deters victims from going to the police. Victims do not see the point in wasting their time with an extremely emotional process if there is not much hope of a conviction and jail time.

Colleges have the responsibility, under Title IX, to take immediate and necessary steps to prevent and eliminate sex discrimination. Once a victim decides to step forward, they have the choice to take their complaint straight to the police and have the criminal justice system handle their case, or file a complaint within the school and have their school administration take charge. These two entities will handle the complaint very differently and will generate different outcomes. School officials do not have the authority to arrest and imprison anyone. Those that are found guilty and expelled from the university are still free citizens and have the ability to rape again. While the criminal justice system has its flaws, it still provides the ability to imprison a perpetrator.

David Cohen, a law professor at Drexel University who has litigated Title IX cases, said there are clearly cases in the criminal justice system where there is abuse of victims. But, he said, “rape is an incredibly serious crime that college administrators aren’t equipped to handle. It’s an issue that very reasonable people disagree about who care deeply about rape survivors and justice”. Ultimately, Cohen said, “If people don’t feel like they can get justice in the system, then they are going to keep it to themselves” (in Hefling, 2014). Since both paths of justice are flawed, it is easy to see why victims are reluctant to step forward.

Only about 20-percent of campus sexual assault victims go to the police. Most college victims choose not to pursue criminal charges for a multitude of reasons. A tenth of them believe that what happened to them is not important enough to bring to the attention of police. This could be because the act was not completed or there was alcohol involved, making the victim falsely believe they were at fault. In addition, victims may be reflecting not their own view of crime, but how they think it will be seen if they report it, according to Laura Dunn, a victim’s rights lawyer and executive director of SurvJustice (Hefling, 2014). There is a clear victim-blaming and dismissive mindset towards sexual assault, especially against college victims.

For those who decide to report their sexual assault to law enforcement, there are different options. Victims may call 911, contact their local police department directly, or visit a medical center. In most areas there are specific law enforcement officers who are trained to interact with survivors of sexual assault. Most agencies participate in Sexual Assault Response Teams (SARTs), which provide a survivor-centered and coordinated response to sexual assault (RAINN, 2009). However, there is a statute of limitations on the window of time that you can report the crime that varies by state, type of crime, and age of victim. In addition, victims are uneasy about reporting to police because they fear it will all be for nothing.

Once the assault is reported to the police, an investigation will begin. This includes an interview by a law enforcement officer, sexual assault nurse forensic exam (rape kit), a longer interview by a detective, an interview of the suspect, investigation into corroborating evidence, and sometimes, the collection of addition physical evidence from the scene (RAINN, 2009). Some victims feel uncomfortable with this process and do not move forward. However, for those who do wish to move forward, the district attorney then decides if there is enough evidence to show beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed the crime. This can be problematic because in many sexual assault situations there are no injuries or hard evidence to prove that sex was nonconsensual and it can turn into a he-said-she-said type of situation.

If the district attorney decides to charge the defendant, the pre-trial proceedings take place. The court will establish bail and bond, at which time it determines whether to keep the defendant incarcerated pending trial, or what amount of money, if posted, will ensure his/her presence at future court proceedings. This can be a scary time for the victim if the defendant posts bail. It allows for an unsafe environment for the victim. The defendant must enter a plea of either guilty, not guilty, or nolo contendere, which means the defendant admits there is enough evidence to prove the assault, but does not admit guilt. The court will also try to resolve evidentiary issues before trial, such as whether evidence should be excluded by rape shield law. The Rape Shield Rule, contained in Federal Rule of Evidence 412 and state counterparts, is a rule preventing the admission of evidence concerning the sexual predisposition and behavior of an alleged victim of sexual misconduct, subject to certain exceptions (Miller, 2012).

Once a case goes to trial, it begins with opening arguments, the prosecution and defense present the evidence, and then there are closing arguments. Each side can present factual and expert witnesses, each of whom is questioned by the prosecutor, and then cross-examined by the defense. Publicly testifying about what happened can trigger traumatic memories for the victims. This is a main concern for victims when choosing to come forward or press criminal charges. After the closing arguments, the jury must come to a verdict of guilty or acquittal. This is a long, drawn-out process that takes time, energy, and is emotionally draining. It is easy to see why many victims do not choose to put themselves through it.

Common reasons victims choose not to report their assault include knowing the perpetrator, the act was not finished, they had been intimate with the perpetrator in the past, there were no injuries, or they are worried law enforcement will not believe them. The last reason is probably the most widespread concern amongst victims. Victims are routinely dismissed not only officially in reported cases, but also through rape culture. Whether it is in every day conversation or expressed subliminally through the media, there is an underlying dialogue amongst society that states women are asking to be raped. This is particularly evident in the college environment that affords young men the opportunity to actively take part in this mission.

For students that decide to file a complaint with the school administration rather than immediately involve the police, it is an entirely different process. I will be using Ramapo College of New Jersey as an example of college policies and procedures regarding sexual assault (college policies in 2015). At Ramapo, victims have several options with respect to reporting. Never, at any time, can a victim’s decision to report or not report be made a condition of receiving other services. At Ramapo, the Assault Contact Team (ACT) is a group of trained professional staff members who provide the campus with victim-centered services and resources for survivors of sexual assault. ACT members are responsible for listening and providing nonjudgmental support to victims. They must review the victim’s rights under the NJ Sexual Assault Victims Bill of Rights. The introduction to the Bill of Rights is as follows:

A college or university in a free society must be devoted to the pursuit of truth and knowledge through reason and open communication among its members. Academic communities acknowledge the necessity of being intellectually stimulating where the diversity of ideas is valued. Its rules must be conceived for the purpose of furthering and protecting the rights of all members of the college community in achieving these ends. The boundaries of personal freedom are limited to applicable state and federal laws and institutional rules and regulations governing interpersonal behavior. In creating a community free from violence, sexual assault and nonconsensual sexual contact, respect for the individual and human dignity are of paramount importance. The state of New Jersey recognizes that the impact of violence on its victims and the surrounding community can be severe and long lasting. Thus, it has established this Bill of Rights to articulate requirements for policies, procedures and services designed to insure that the needs of victims are met and that the colleges and universities in New Jersey create and maintain communities that support human dignity (NJSA 18A, Chapter 61E).

These rights apply to victims of sexual assault that occur “on campus of any public or independent institution of higher education in the state of New Jersey, where the victim or alleged perpetrator is a student at that institution, or when the victim is a student involved in an off-campus sexual assault.” The Bill of Rights also contains human dignity rights, which include the right for victims to be free from pressure from campus personnel to “report crimes if the victim does not wish to do so; report crimes as lesser offenses than the victim perceives the crime to be; refrain from reporting crimes; refrain from reporting crimes to avoid unwanted personal publicity” (Campus Sexual Assault Victim’s Bill of Rights, 2004).

Students must also be made aware of their rights to resources on and off campus, which include medical, counseling, mental health and student services for victims of sexual assault, whether or not the crime is formally reported to campus or civil authorities. Victims must be afforded the same access to legal assistance as the accused, as well as the ability to have others present during any campus disciplinary proceeding. Victims also must be notified of the outcome of the sexual assault disciplinary proceeding against the accused. Unfortunately, there have been many cases recently in which victims say they were not notified.

At Ramapo College of New Jersey there are options for reporting a sexual assault. Students have the choice of contacting an ACT member or filing an incident report with Public Safety. As mentioned before ACT members are responsible for discussing a victim’s options. Victims have the option to not make an incident report of any kind, although an anonymous crime report must be filed in order to comply with federal regulations. There is also a hidden clause in this option:

If the incident is deemed to pose a significant threat to public safety, the college may choose to pursue a third party investigation, or to issue a public warning. In either case, the incident report is limited to necessary college personnel, and in any public warning, no names are released. The victim cannot be pressured to participate in any investigation that the college chooses to undertake (Ramapo ACT FAQ, 2015).

If a victim discloses their assault to a college faculty member other than an ACT member, the staff must also file an anonymous crime report form, even if the victim does not wish to file an incident report. Although there are clear positive outcomes from this procedure, it may be betraying the trust the victim has in the faculty member they sought out. Victims want to feel safe when discussing their incident. If they have no desire to file a report, they could feel deceived, scared and embarrassed if the incident is published, even if they are not named. Knowing that their assault is written down somewhere against their wishes can cause intense trauma for the victim.

If a victim chooses to file an incident report with Public Safety, the Mahwah Police Department is automatically and immediately contacted. Filing a report means that victims must speak to a detective from Mahwah PD and possibly the Bergen County Prosecutor’s office. It is easy to see why victims may be reluctant to file a report. There are so many people and entities that get involved once they decide to file. It can be overwhelming and cause victims to reconsider if the process is worth the stress, especially since the chances of seeing their perpetrator behind bars is slim. At this point Public Safety will follow the medical protocol to see if immediate medical attention is necessary. A Sexual Violence Resource Center advocate will be available to the victim. This advocate will be by the victim’s side during interviews, in the hospital, and at appointments. It is important to support the victim in all aspects of their journey to justice. Simply holding their hand during an interview can give them the confidence to follow through with the case.

Evidence from the crime scene will be collected and given to the prosecutor’s office. Victims will be asked to give a statement and asked if they would like to proceed with pressing criminal charges. This is the only venue for a victim to press charges. Law enforcement will have the ability to charge the perpetrator and the Vice President for Student Affairs (VPSA) will review the case. The VPSA will make a determination as to how to reprimand the accused. Just as the perpetrator has a right to a fair trial in court, the victims have a right to a judicial hearing at school as well. However, school officials are less equipped to handle such sensitive cases, which results in a lack of appropriate action. Violations are determined using the “preponderance of the credible evidence” standard, which is a lower standard than “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Therefore, it is easier for a student victim to succeed in an administrative hearing than a criminal trial. However, if a victim does not file an incident report, it takes away any opportunity to seriously punish the perpetrator. A student may be deemed responsible for a sexual assault by their school administration and merely face a temporary suspension with no criminal charges. It is for these reasons that victims have trouble deciding in which setting to pursue their case, if any.

Although victims’ rights are plainly and carefully spelled out in the official school documents, many times procedures are not as diligently carried out. School administrators only have so much power to punish the offender, and even when they do the punishments are often times not harsh enough or safe for the victim.

Students found responsible for sexual assault were expelled in 30-percent of cases and suspended in 47-percent of cases, according to The Huffington Post’s review of data collected from nearly three-dozen colleges and universities. At least 17-percent of students received educational sanctions, while 13-percent were placed on probation, sometimes in addition to other punishments (Kingkade, 2014). While most people would agree at the very least those found guilty of sexual assault should be banned from campus, it is evident that the majority of perpetrators are barely reprimanded. Not even a third of college students found guilty of sexual assault were kicked out of school. This is partly due to institutions worrying more about hurting the perpetrators and their image than helping the victim cope and seek justice.

The Association for Student Conduct Administration (ASCA) sets guidelines for schools to follow. Although the ASCA does not outright declare what punishments should be meted out, it does distribute literature emphasizing that “campus proceedings are educational” and “the process is not punitive” (Kingkade, 2014). The organization recommends that “legalistic language,” such as “rape,” “judicial,” “defense” or “guilty” should be removed from policies and procedures. When these words are detached, it also takes away from the significance of the crime committed against the victim. The President-elect of ASCA, Laura Bennet notes, “Rape is a legal, criminal term. We’re trying to continue to share we’re not court, we don’t want to be court – we want to provide an administrative, educative process” (in Kingkade, 2014). While it is clear that school officials are not police officers and attorneys, sexual assault is a crime and should be treated as such no matter the venue.

This type of lessened attitude towards the harshness of the crime is extended when universities use phrasing such as “nonconsensual sex” to represent sexual assault. The language adds to the dismissive, passive culture surrounding campus sexual assault. Mislabeling rape allows institutions to keep crime numbers lower than they really are and to appear safer. Downplaying sexual assault allows for looser punishments and less victims confidently stepping forward. Over 3,100 American universities follow ASCA guidelines. ASCA membership has been growing rapidly ever since the U.S. Department of Education issued a Dear Colleague letter to all colleges in April 2011, telling them they must adjudicate sexual assault cases on campus. In the Huffington Post study, Wesleyan University found 9 individuals to be responsible of sexual assault from 2009-2012, but expelled/dismissed none of them. Four were suspended and three were put on probation. It is clear that being found guilty does not necessarily mean punishment. Schools are only allowing for more sexual assaults to occur by permitting rapists to continue their education on campus.

One example of schools taking an educational approach rather than a punitive one to campus sexual assault is the case of Tucker Reed at University of Southern California in 2013. Reed was sexually assaulted in 2010 and told by school officials that the goal was not to “punish” her rapist. “Rape is not an educative experience. It is a crushing, life-altering, inhumane violence,” according to Reed. She filed a formal complaint with the U.S. Department of Education, claiming USC’s administration failed to respond adequately to the assault. Three other similar cases from prestigious schools that failed to properly adjudicate campus sex crimes joined the complaint. The complaints say the schools violated students’ civil rights by not thoroughly investigating sexual assaults, and failed to obey the Cleary Act, a federal law that mandates the accurate tracking and public disclosure of crime statistics on campus, including sex offenses (Kingkade, 2014).

James Madison University punished three fraternity members for sexually assaulting a female student and sharing their video of the attack by banning them from campus – after they graduated (Kingkade, 2014). The lack of punishment and justice for the victim sends a message to the campus community that rape is an excusable, minor offense, which will not affect your ability to graduate. The punishment, or lack thereof, allows the perpetrators to sexually assault other female students, while finishing their degrees. The victim filed a complaint to federal officials about the handling of the case, which led to an investigation by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. JMU violated the gender equity law of Title IX. The school did not take enough steps to ensure campus safety or offer the victim a safe work environment. The victim withdrew from JMU because her grades had slipped, which caused her to lose financial aid. The lack of proper action and harmful decision-making by school administrators, who are poorly equipped to handle sexual assault cases, led to a helpless victim. Despite having video evidence of her attack, the victim still had to see her perpetrators around campus.

In many cases not only are those found guilty of sexual assaults unsuitably reprimanded for the level of their crime, but they are also given more protection than the victims. Al Jazeera America viewed logs from 15 New York City colleges recording crimes over four years (from January 2010 to September 2014) and interviewed five survivors. Official school records contained numerous inaccuracies, including no mention of assaults that were reported (Dhir, 2015). Two NYU students’ complaints were reported to school officials but do not appear on the books. Due to the fact that both of these students decided not to file a report to campus public safety, their reports do not show up on NYU’s crime log. Schools want to maintain a certain image and therefore do not want to publish any information that can shed negative light on them. However, the victims feel betrayed and helpless. It is as if it never happened because the schools erased it from their logs. This type of action speaks volumes for the dismissive atmosphere of administration towards sexual assault victims.

Only 43-percent of sexual offenses reported on New York City’s college campuses met with some form of discipline (Dhir, 2015). Part of the problem with campus police handling sexual assault cases is that public safety officers at many schools are not licensed, which means they cannot conduct criminal investigations or make arrests. This means that even if a victim reports the crime and the perpetrator is found guilty, the most justice that can be served is expulsion. Campus public safety does not have the ability to incarcerate or charge those guilty of sexual assault. Only law enforcement holds the ability, which means victims must go through that process separately.

Female students are being sexually assaulted in appalling numbers and colleges are allowing rapists to continue their education. The claim from many colleges that an educational approach to rape is appropriate is twisted and detrimental. Forced by the federal government, colleges are conducting rape trials more often. Failing to punish rapists adequately demeans the assault and the victim. Research suggests that more than 90-percent of campus rapes are committed by a relatively small percentage of college men – possibly as few as 4-percent – who rape repeatedly, averaging six victims each (Rubenfeld, 2014). Therefore, it is imperative that when women do step forward, they are believed and the incident is investigated. The victim might be able to help prior victims get justice. However, this justice is dependent on the administrative response. If the assailant is found guilty and not expelled, the female population, including past victims of the school are now at risk for future assaults.

Conclusion

The central issue of campus sexual assaults is the lack of justice for victims. A small percentage of victims of sexual assault report their perpetrator and those that do are routinely dismissed. Perpetrators are not punished but rather slapped on the wrist and told not to do it again. Some schools are stricter on plagiarism than rape. Why is there some sort of shield over each campus protecting rapists? A heinous crime should not be downgraded just because it took place in certain institutions or because the perpetrator/victim is a student.

Institutions should not be responsible for the investigation, hearing, and punishment of individuals accused of rape. Rape is one of the most serious crimes a human can commit. Campus police should immediately notify the local police department in order to allow trained professionals to handle the sexual assault. In addition, law enforcement needs to treat each case with utmost importance. There are far too many cases that have botched investigations, utilized victim-blaming tactics, or lacked proper punishment. Colleges should have never been put in charge of hearing sexual assault cases. Without the authority to charge and imprison guilty perpetrators, school officials are rendered powerless and guilty verdicts are meaningless.

Alexandra Brodsky, a student at Yale law school and an organizer at Know Your IX, a grassroots organization that educates sexual assault survivors about their civil rights in the college setting, illustrates the tension between police and colleges: “When I reported violence to my school, I was told not to go to police” (Bolger, 2015). There is no clear-cut model for the victims that underlines what happens after they report their assault. Sexual assaults are treated on a case-by-case basis. There should be universal rules for how colleges deal with sexual assault. Perpetrators and victims should be aware of what will happen to them after an assault is reported. Yet in whichever venue victims chose to report their assault, with the police or the school, it seems as though they are put on the backburner.

Colleges and universities are putting their image first and foremost to attract new applicants. They are a business and do not want to miss out on incoming students and their money by making headlines for sexual assaults. Parents will not send their sons and daughters to schools that report high rates of sexual assault. In addition, schools may only be complying with regulations out of fear that they will lose federal funding. The victims are not a main concern to colleges.

In the past couple of years there has been more exposure to the multitude of sexual assaults occurring at universities nationally. The most infamous source of media coverage on the issue was the Rolling Stone’s expose of an alleged University of Virginia gang rape of a female first year student. The author of the piece, Sabrina Erdely, did not uphold journalistic standards. She based all of her writing on one unnamed source. It turned out that the source was not reputable and Rolling Stone was forced to retract the story. This was extremely unfortunate because the article became so popular. It is a slap in the face to victims everywhere. Victims have always been dismissed by society, but now there is an enhanced stigma surrounding sexual assaults.

Erdely created a situation in which she is adding to the perception that sexual assault does not happen, because that perception is a reality. There is a culture that believes sexual assault does not occur on college and university campuses. While it is evident that there is no truth to this belief, media exploitation of false allegations gives the population ammunition. Victims and future victims of sexual assault are now facing a greater fear of not being believed. The article did a disservice to those falsely named, as well as to real victims. The dismissive culture of sexual assault is heightened when false accusations are given media attention.

Although there are federal regulations set up to promote gender equality and prevent gender-violence in college, there are clear limitations. They only apply to schools that receive federal funding and most of the guidelines are mere recommendations. The universities often seem more concerned with upholding their reputation than helping victims of sexual assault. Sexual assaults need to be taken seriously and handled with care for the right reason. Schools should not be responsible for conducting sexual assault hearings. Without the authority to punish the perpetrator, the hearing is merely mocking justice.

The nature of judicial hearings adds to the overall dismissive culture of sexual assault. There is guaranteed prison time for those convicted of rape across the United States. How can a crime equate to jail time everywhere but college campuses? There should be no exception to college rapes. A victim is a victim no matter where the assault occurs. We, as a college collective, need to shine a light on the imperfections of our institutions’ response to gendered violence and demand more.

References:

Armstrong, Elizabeth A., Laura Hamilton, and Brian Sweeney. (2006).

Sexual Assault on Campus: A Multilevel, Integrative Approach to Party Rape. Social Problems, 53(4), pp. 483-499.

Bolger, Dana. (2015). Title IX: The Basics. 9 Things to Know About Title IX. Retrieved from http://knowyourix.org/title-ix/title-ix-the-basics/.

Campus Safety Magazine. (2015). How to Comply with the Department of Education’s Title IX Sexual Violence Guidance. Retrieved from http://www.campussafetymagazine.com/article/How-to-Comply-With-the-Dept-of-Ed-s-Title-IX-s-Sexual-Violence-Guidance.

Chemaly, Soraya. (2013). Why Is UConn’s Mascot a Popular Rape Meme? The Huffington Post, April 26. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/soraya-chemaly/why-is-uconns-mascot-a-po_b_3165756.html.

Chemaly Soraya. (2013b). 6 Critical Reasons to Rethink Football and Kids, The Huffington Post, February 2. Retrieved from

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/soraya-chemaly/youth-football_b_2647601.html.

Chmielewski, A. (2013). Defending the Preponderance of the Evidence Standard in College Adjudications of Sexual Assault. Brigham Young University Education and Law Journal, 143.